Volume 4 Issue 1

By Abigail Huggett, Trinity Sixth Form Academy

Citation

Huggett, A. (2024) Intra-plate volcanism, geology and hazard management at the Long Valley Caldera, California. Routes, 4(1): 27-38.

Abstract

This essay evaluates the role of intra-plate volcanism in shaping the landscape of the Long Valley Caldera in California. It also evaluates approaches to the management of these processes that have enabled humans to live in the place with less risk from the hazard. The article identifies the Long Valley Caldera as a useful case study for geography education because of how it combines a variety of tectonic and volcanic hazards with an interesting case study of hazard (mis)management.

Key Terms

Key Terms

Scoria cone: Also called a cinder cone, a scoria cone is a steep conical hill of loose pyroclastic fragments. These can come in the form of volcanic ash or volcanic clinkers. Pyroclastic fragments are formed by explosive eruptions or lava fountains from a single vent.

Caldera: A large volcanic crater, formed by a major eruption, leading to the collapse of the mouth of the volcano.

Fumaroles: A fissure which emits steam and volcanic gases. These gases can be carbon dioxide or sulfur dioxide.

Basalt: A dark coloured igneous rock which has a runny consistency. This kind of lava builds shield volcanoes when erupted.

Rhyolite: An extrusive igneous rock which is high in silica content and when in molten form has quite a sticky consistency.

Intra-plate Volcanism: Volcanism that takes place away from the margins of tectonic plates.

1. Introduction – what is intra-plate volcanism?

Intra-plate volcanism is when magma from a mantle plume in the asthenosphere upwells and pierces the surface of the Earth through fissures (Newstead, 2004). As a result of intra-plate volcanism, a landform called a volcanic chain can be created. This is when processes of tectonic plate movement cause the plate above a mantle plume to move, creating a line of extinct volcanoes that have been formed by the motion of the plate over the plume. A new active volcano is created in its place over the plume, leading to the formation of a resurgent dome. This type of volcanism most commonly produces shield volcanoes which are gradual-sloped and erupt basaltic lava. However, they can also form calderas, and this is the situation in the example that is the focus of this essay – Long Valley, California.

Volcanism in this area is interesting because it is lesser known than other examples of intra-plate volcanism like Yellowstone, or the Hawaiian volcanic island chain. As this essay will show, the historic geology of the area is fascinating as super-volcanic eruptions have taken place (British Geological Survey, n.d.), and intra-plate volcanism has played a significant role in shaping both the human and physical geography of the place.

2. Location and geographical context of Long Valley

The Long Valley is located in Eastern California, along the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada mountains. The Long Valley mountains were formed by eruption around 40 million years ago (Traer, 2015). The geology of the area is composed of mostly rhyolite. The Mono-Inyo crater volcanic chain is moving in a south-eastwardly direction towards the town of Mammoth lakes (Long Valley Caldera, n.d.). The town is mostly known for skiing during the winter but is a popular tourist location in the summer for its scenic views and diverse alpine wildlife. There are many faults across the Long Valley which are perpendicular to one another. These faults can cause earthquakes which vary between the magnitudes of 3-5 on the moment magnitude scale, but sometimes can range up to a magnitude of 7.6, which would cause major damage in populated areas, such as Mammoth Lakes (Hill et al., 2000). In an area which is regularly used for skiing, this might cause avalanches, therefore posing a risk to life and the economy.

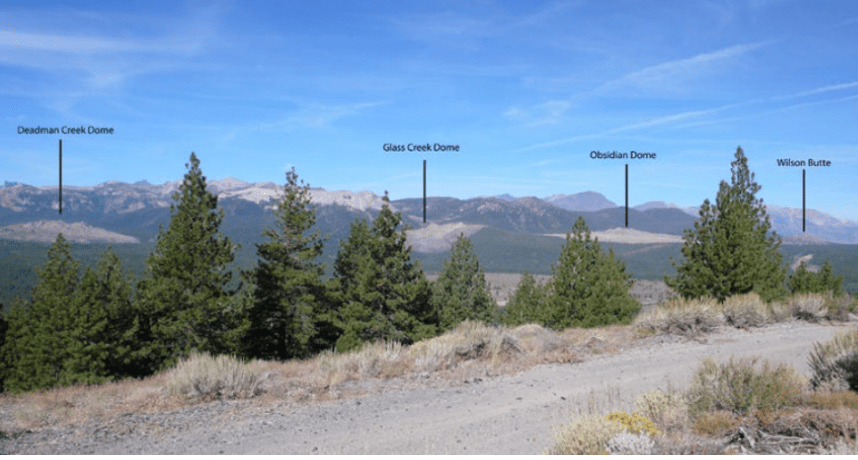

Figure 1: An annotated photograph to show the presence of extinct volcanoes in the Long Valley. Source: https://www.usgs.gov/volcanoes/long-valley-caldera/long-valley-caldera-field-guide.

Figure 1 shows that there are four significant volcanic landmarks in the Long Valley called Wilson Butte, Obsidian dome, Glass Creek dome and Deadman Creek dome. They were all created in the Mono-Inyo eruptions which took place in 1350 CE (Common Era). This is known to be one of the most substantiated prehistoric eruption dates in the world (Long Valley Caldera, n.d.).

3. How do calderas form?

A caldera is a large depression in the ground’s surface, which is formed when magma present in a magma chamber is expelled through an explosive eruption (Natinal Geographic, n.d.). The cavern created by the expulsion of magma from the magma leads to a collapse in the volcano, creating a bowl-shaped depression in the surface. In the case of Long Valley, this process took place 760,000 years ago, when the volcano collapsed in on itself after great volumes of magma were ejected. This created the 18-mile-long bowl-depression, which is known today as the Long Valley.

4. Volcanism, geology and human uses of the Long Valley Caldera

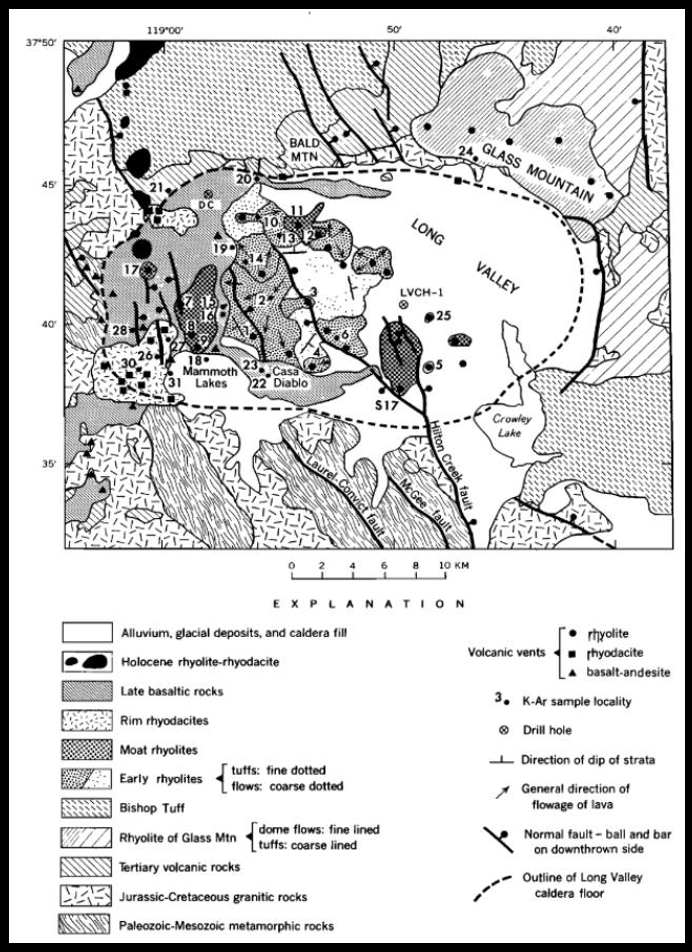

In Eastern California, the Long Valley volcanic chain has been lying dormant for the past 100,000 years. Volcanologists have identified that there is a magma plume underneath the surface which extends 240 cubic miles beneath the rigid crust (Hill et al., 2000). As shown in Figure 2, Mammoth Mountain’s peak is the apex of the Mono-Inyo craters and was formed by a series of eruptions which ended 50,000 years ago (Hill et al., 2000).

Figure 2: A map to show the rock composition, volcanic zones and seismic features of the Long Valley Caldera (Bailey et al., 1976).

The caldera has a geological record of large eruptions, some of which scored very high on the volcanic explosivity index (VEI). The latest significant eruption took place around 760,000 years ago and had a magnitude of 7 on the VEI. This was called the Bishop eruption, and formed what is called Bishop Tuff. The eruption destroyed Glass Mountain, composed of obsidian, which was located around 20km away from the volcano. Around 600 cubic kilometers of material was blasted out of the vents, creating a large caldera. As most of the tephra from the blast was blown directly upwards, the initial 2-3km deep depression was filled around 2/3 full. Eruptions over the past 3 million years have been crucial to shaping the craggy mountains surrounding the Long Valley, and also contributed to soil fertility that helps crop growing.

Figure 3: An image to show an extinct fissure which is located in the Long Valley. My own image taken from a fissure at Mammoth Lakes.

There has been confusion of some geological features in the area. Figure 3 shows an extinct fissure which was formed around 600 years ago by one of the recent Mono-Inyo eruptions. Geologists first thought the fracture was related to earthquake activity. More recent work by local geologists has proven it to be a fissure. The fissure is 60 feet deep and permafrost sits at the bottom. The residence of permafrost provides evidence that this fissure is in fact extinct. As the land surface moves over the mantle plume, fissures open up along the upwelling zone and then move off the direct point of the plume over time. These fissures release volcanic gases and create geysers where there are bodies of water. These are scattered across the Long Valley.

In 1990, there were increased reports of trees dying off in areas of Mammoth Mountain. USGS research discovered that this was caused by large amounts of carbon dioxide and other volcanic gases seeping through the soil (Mammoth Mountain, n.d.; Edmonds, Grattan and Michnowicz, 2018: 73). Death is caused as plants need to absorb oxygen from their roots. It also denies them nutrients. These gaseous releases are harmful to humans given the extremely high concentration. Breathing air with more than 30% carbon dioxide concentration can cause unconsciousness and potentially death. Volcanic smog is also known as ‘vog’. These gaseous releases have caused changes in human behaviour in the area (Edmonds, Grattan and Michnowicz, 2018). For instance, snow cave camping was popular for years but is now not advised, as carbon dioxide can be trapped in large concentrations within snowpacks in winter months. This has shaped patterns of human settlement in the Long Valley, as there are only certain areas of the valley where humans can inhabit, without the risk of volcanic gas poisoning.

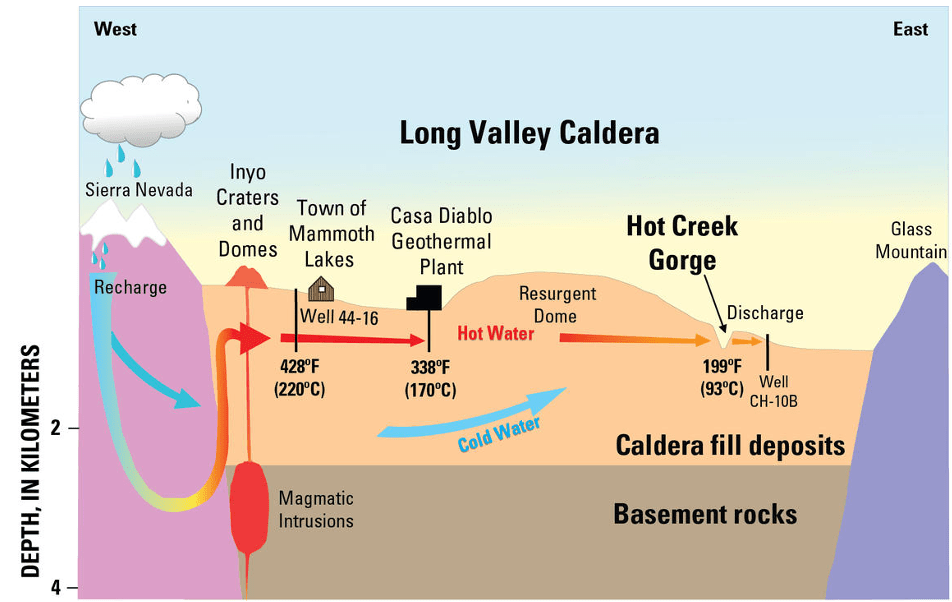

Figure 4: A diagram to show the relative location of the Casa Diablo geothermal plan and how it uses magmatic intrusions to function. Source: https://www.usgs.gov/volcanoes/long-valley-caldera/hydrothermal-monitoring-long-valley-caldera.

A geothermal plant is a source of renewable energy that uses pipes to pump water underground under high pressure in order to turn it into steam (USGS, n.d.). Casa Diablo geothermal plant will produce renewable energy for the town of Mammoth Lakes and is currently under construction. Figure 4 shows how it will be located on the flanks of the resurgent dome and is recharged mostly by snowmelt in the Sierra Nevada highlands. The snowmelt, heated by geothermal energy, will power the plant. The plant will power 22,000 homes for Eastern California and offset 160,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide annually. The plant will also create over 180 new jobs in construction for the people of Mammoth Lakes while it is being built (Richter, 2021).

Areas in the Long Valley also contain some interesting geological features which intrigue and attract tourists to the area.

Figure 5: An image to visualise the column formations at Crowley Lake, Long Valley. Source: https://www.lakescientist.com/mystery-of-crowley-lake-columns-solved/.

For instance, Crowley Lake is located on the south-eastern fringes of the Long Valley. Figure 5 shows the columns on the edge of the lake. They were created by cold snowmelt percolating down into the rock layer and steam from the heated lake rising up into it. Various minerals like gold, silver, kaolin and iron were contained in the water, so when the water had been heated by the ground, this caused a small-scale convection process which allowed these minerals to precipitate out. This formed veins of deposited minerals in the upper rock layer. Over time, the weaker parts of the rock, which didn’t contain as many minerals, were weathered and eroded. This left behind thin vertical columns which are composed of various minerals, and can be seen in figure 5 (Kirchner-Smith, n.d.).

Figure 6: Columnar basalt formations in the Long Valley, also known as the Devil’s Postpile. Source: https://thatadventurelife.com/2020/08/11/devils-postpile-national-monument-mammoth-lakes-ca/.

Figure 6 shows the Devil’s Postpile. It is a type of geological formation caused by lava flow processes just less than 100,000 years ago (National Park Seevice, n.d.). The columnar basalt formations have been made from lava cooling. The smooth flowing basalt, when in molten form, starts to form (typically hexagonal) chunks at the surface as it starts to cool. As it cools, the lava cracks into these 120-degree angle patterns vertically. This process is called crack propagation.

5. Seismicity and the Long Valley Caldera

There has been no recent volcanic activity in Eastern California. However, earthquakes have occurred. Earthquakes have been caused by a combination of tectonic fault movements and pressure accumulation from rising magma beneath the surface. In Mono county, in the last 200 years, earthquakes have taken place with up to a magnitude of 7.6. A period of unrest began in the year of 1978 after a magnitude 5.4 earthquake took place at the fault line which is located 6 miles South-East of Mammoth Lakes. There was a very intense period of unrest in May of 1980, where there were four magnitude 6 earthquakes in one day. This resulted in more geological examination of the area, and monitoring systems have been put in place (Hill et al., 2000).

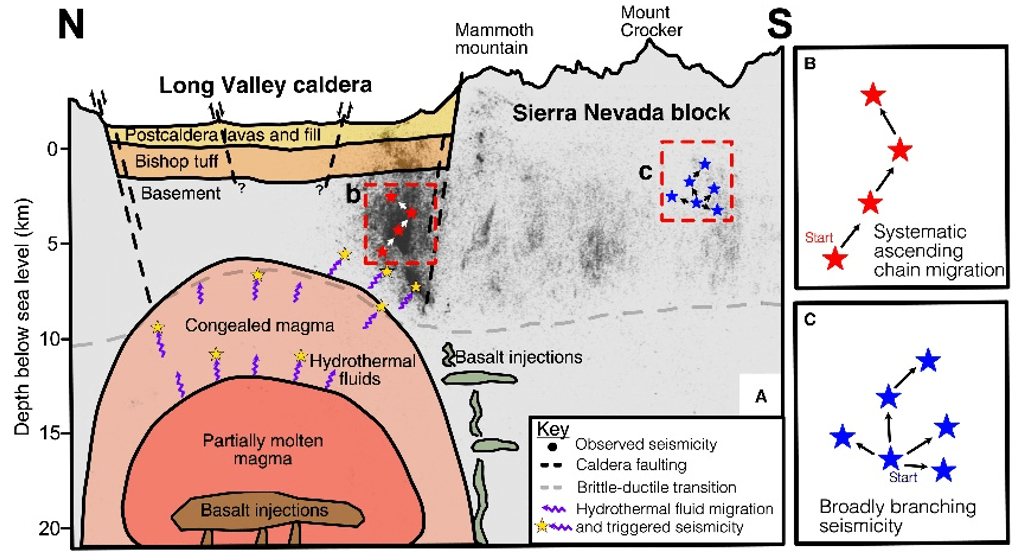

Figure 7: A diagram to show the subsurface geomorphology of the Long Valley Caldera. Source: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abi8368.

6. Monitoring and managing the Long Valley caldera

The US Geological survey has planned stages of responses to potential seismic activity of different magnitudes. These are as follows:

Currently, there is only vague forecasting for any upcoming volcanic activity in the valley. The US Geological Survey claim that the odds of an eruption yearly are only up to 1% chance, meaning one is highly unlikely to take place. If there was to be an eruption, they claim that there would be a lava fountaining eruption, building a scoria cone. However, they are sure that there will be frequent seismic swarms. In the past 5,000 years, volcanic activity in the valley has been mostly effusive. Only three of the estimated twenty eruptions have been explosive. These explosive events, when they do occur, tend to be described as small to moderate in scale (Hill et al., 2000).

Getting hazard management communication right in areas like the Long Valley is especially important. The community has vulnerabilities associated with tourism and an eruption would cause media hype, following a loss of reputation for the USGS and other geological organisations (Hill, Mangan and McNutt, 2018: 171). The dangers of miscommunication are evidenced by events of 1982, when a ‘Notice of Potential Volcanic Hazards’ appeared in the Los Angeles Times two days prior to the Memorial Day weekend, impacting on local tourism-focused businesses and leading to a breakdown in trust between residents and the US Geological Survey. As academic researchers have noted, ‘The local response was one of outrage, anger and disbelief’, and ‘Geologists, and USGS employees in particular, immediately became persona non grata in Mammoth Lakes and Mono County – an attitude that only gradually mellowed over the years’ (Hill, Mangan and McNutt, 2018: 176). So strained did relations become that there were even ‘Geologists not welcome’ signs put up in local motels and restaurants! (Hill, Mangan and McNutt, 2018: 185).

7. Conclusion: understanding intra-plate volcanism at the Long Valley caldera

Intra-plate volcanism, and associated events, have shaped not only the physical features of the area, but also the inhabitants within. The Long Valley continues to fascinate researchers to this day from its iconic landmarks to natural phenomena. The existence of a mantle plume beneath has created opportunities for both geothermal energy and tourism, leading to economic benefits for local residents. Nevertheless, these benefits exist in tension with continuing risks, including from gaseous releases, seismicity and even vulcanicity. These risks have not always been managed and communicated effectively, as shown by the way that geologists lost the trust of the local community when they miscommunicated the likely scale and nature of the risk of a volcanic event in the area in 1982.

In geography classrooms, intra-plate volcanism is too-often only associated with the ‘flagship’ examples through which it is often taught, such as Hawaii and Yellowstone. The Long Valley caldera is worthy of further study and consideration as an educational resource for geography classrooms because of how it combines a variety of tectonic and volcanic hazards with an interesting case study of hazard (mis)management. While there remains ‘the threat of an impending volcanic eruption’ at Long Valley, it is for hazard managers to try to balance the risks of an ‘over-anxious response’ that would upset local residents and break trust once more with the opposing risk of an ‘overly conservative response’ that could lead to serious casualties and fatalities should the volcano erupt (Hill, Mangan and McNutt, 2018: 185).

Acknowledgements

With great thanks to Dr Whittall, who has always encouraged, supported and provided constructive criticism upon my work. This essay would not have been created without this valuable encouragement.

References

Bailey, R.A., Dalrymple, G.B. and Lanphere, M.A. 1976. Volcanism, structure, and geochronology of Long Valley Caldera, Mono County, California. Journal of Geophysical Research, 81(5): 725–744. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/jb081i005p00725.

British Geological Survey. n.d. Geothermal energy, [online]. Available at: https://www.bgs.ac.uk/geology-projects/geothermal-energy/.

Edmonds, M., Grattan, J. and Michnowicz, S. 2018. ‘Volcanic gases: Silent killers’, in Fearnley, C., Bird, D., Haynes, K., McGuire, W. and Jolly, G. 2018. Observing the Volcano World: Volcano Crisis Communication Springer: pg 65-84.

Hill, D., Bailey, R., Sorey, M., Hendley, J. and Stauffer, P. 2000. ‘Living with a restless caldera: Long Valley, California’, US Geological Survey Fact Sheet 108-96, available online at https://pubs.usgs.gov/dds/dds-81/Intro/facts-sheet/fs108-96.html (last accessed 21st July 2022).

Hill, D., Mangan, M., and McNutt, S. 2018. ‘Volcanic unrest and hazard communication in Long Valley volcanic region, Califronia’, in Fearnley, C., Bird, D., Haynes, K., McGuire, W. and Jolly, G. 2018. Observing the Volcano World: Volcano Crisis Communication Springer: pg 171-188.

Kirchner-Smith, M. n.d. ‘The effects of hydrothermal processes on groundwater and mineral deposition in the Eastern Sierra Nevadas’, available online at https://sierra.sitehost.iu.edu/papers/2010/kirchner-smith.html (last accessed 21st July 2022).

Long Valley Caldera. n.d. ‘Long Valley Caldera Field Guide’, available online at https://www.usgs.gov/volcanoes/long-valley-caldera/long-valley-caldera-field-guide (last accessed 21st July 2022).

Mammoth Mountain, n.d., ‘Volcanic gas monitoring at Mammoth Mountain’, available online at https://www.usgs.gov/volcanoes/mammoth-mountain/volcanic-gas-monitoring-mammoth-mountain (last accessed 21st July 2022).

National Geographic. n.d. ‘Calderas’, available online at https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/calderas (last accessed 21st July 2022).

National Park Service, n.d. ‘Geology at Devils Postpile National Monument’, available online at https://www.nps.gov/depo/learn/nature/geology.htm#:~:text=Current%20studies%20suggest%20that%20the,California%20was%20a%20shallow%20sea (last accessed 21st July 2022).

Newstead, L. 2004. ‘Geofile online: Geological slant on plates’. Available online at https://www.watfordgrammarschoolforgirls.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Geological-slant-on-plates.pdf (last accessed 21st July 2022).

pubs.usgs.gov. (n.d.). Where Will Volcanoes Erupt in California’s Long Valley Area? Volcano Fact Sheet. [online] Available at: https://pubs.usgs.gov/dds/dds-81/Intro/facts-sheet/futureeruptions.html.

Richter, A. 2021. ‘Construction underway for Casa Diablo-IV geothermal plant, California’, available online at https://www.thinkgeoenergy.com/construction-underway-for-casa-diablo-iv-geothermal-plant-california/?amp=1 (last accessed 21st July 2022)

Richter, A. .2021. ‘Construction underway for Casa Diablo-IV geothermal plant, California’, available online at https://www.thinkgeoenergy.com/construction-underway-for-casa-diablo-iv-geothermal-plant-california/?amp=1 (last accessed 21st July 2022).

Traer, M. 2015. ‘Stanford scientists crack mystery of the Sierra Nevada’s age’, available online at https://news.stanford.edu/2015/12/11/mountains-even-older-121115/#:~:text=According%20to%20Mix’s%20study%2C%20the,refer%20to%20as%20the%20Eocene (last accessed 21st July 2022). UDGS. n.d. Long Valley Caldera | U.S. Geological Survey, [online]. Available at: https://www.usgs.gov/volcanoes/long-valley-caldera#:~:text=The%2016%20x%2032%20km,%22)%20about%20760%2C000%20years%20ago. [Accessed 4 Jan. 2023].

#Write for Routes

Are you 6th form or undergraduate geographer?

Do you have work that you are proud of and want to share?

Submit your work to our expert team of peer reviewers who will help you take it to the next level.

Related articles