Volume 4 Issue 2

By James Swallow, University of York

Citation

Swallow, J. (2024) Urgency not anxiety: effectively educating about climate change to empower action and avoid distress. Routes, 4(2): 77-95.

Abstract

Effective climate change education is important in creating a more sustainable future. Education about climate change, if framed negatively, can contribute to climate anxiety. This may have negative impacts on an individual’s wellbeing, as well as reduce their ability to act against climate change. Following a review of the existing literature, three key strategies are presented for reducing this anxiety. Firstly, solutions-oriented education, especially through a local lens can be useful. Secondly, fostering hope through a supportive learning environment, such as open discussion and emotional mediation supports a healthier response to climate change information. Thirdly, embracing the uncertainty of climate science as well as attempting to vision a climate-altered world can help individuals to feel more positive about the future. Educators should explore these strategies to inspire action against climate change and improve the resilience of individuals.

1. Introduction

Climate change is one of the greatest threats facing society. Effective action is required to address the issues that are emerging (Pedde et al., 2019). The IPCC (2018) argues that we must keep temperature increases to under 1.5°C, although this is becoming increasingly unlikely (Armstrong McKay et al., 2022). UN Secretary-General António Guterres (2021, n.p.) makes clear ‘there is no time for delay and no room for excuses.’ One way to inspire change is through education (Nerlich, Koteyko and Brian, 2009). However, with continuing environmental degradation (Brondizio et al., 2019), ensuring that those engaging with climate change have the resilience to contribute to meaningful action is crucial. Climate change, either through its direct effects or by creating persistent worry can contribute towards mental ill health (Pihkala, 2020). Recently, terms under the “climate psychology” umbrella have been coined to describe these phenomena; notably, “climate anxiety” (Ibid.). Research has identified ways of defining, measuring, and treating climate anxiety (Larionow et al., 2022). Although, as with all mental ill health, prevention is better than getting to the point of needing treatment (Arango et al., 2018). Educating about the climate crisis in a way that avoids unnecessary distress could be an important way of reducing instances of climate anxiety.

This paper aims to suggest strategies for educators to reduce instances of climate anxiety. A literature review was conducted around the themes of climate anxiety, education, and empowering action. Firstly, the importance of climate literacy is discussed, before giving an overview of climate anxiety and its effects. Three key suggestions are made about how to educate about climate change; these are: solutions-based teaching, hope generation and embracing uncertainty. Case studies were sought for each strategy, to provide examples of translating theory into practice.

2. Background

2.1 The importance of climate literacy

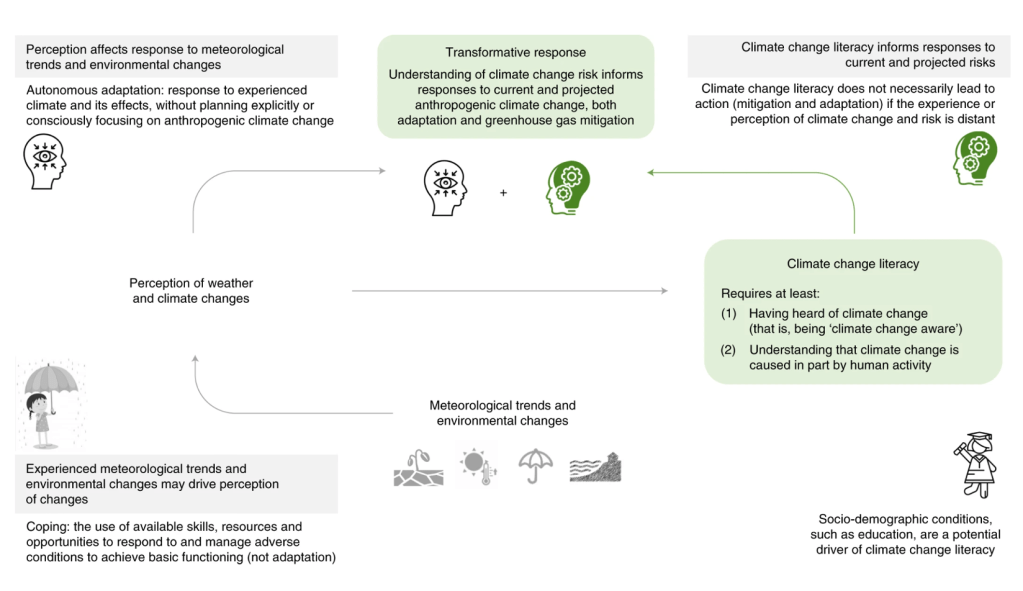

Climate literacy describes the ability to understand and apply knowledge about climate change. Miléř and Sládeka (2011) propose four pillars of climate literacy: understanding climate, recognising reputable information, communicating about climate (change) meaningfully, and making informed decisions regarding climate (i.e., “action”). Ensuring individuals understand climate change, and their impact on the environment, can foster conscious decision-making, potentially instilling pro-environmental behaviours. Figure 1 shows that a person’s response to climate change is influenced by their level of climate literacy. A more-informed person can recognise the effects of climate change and understand the action they can take. Whereas, a less-informed person relies on automatic and heuristic responses, which leads to ‘coping’ rather than transformation. However, it is important to note that knowledge does not necessarily result in action (Frick et al., 2021). Individuals must feel empowered to act, using the knowledge they have gained. For example, through Jensen and Schnack’s (1997, p.173) Environmental Action Competence framework, where they argue that four strands are necessary from environmental education to create effective action: ‘knowledge, commitment, visions, and action experiences.’ However, knowledge is the foundation of this framework, so it is important to have the underlying literacy in place to guide effective action.

Figure 1: proposed responses to climate change as a result of improved climate literacy (Simpson et al., 2021)

Climate change education (CCE) which empowers, is seen as integral to climate action (UNFCCC, 2022, p.1), and is included in the UN’s (2015) Sustainable Development Goals. In the UK, work is being done to integrate CCE into the curriculum through the development of the Natural History GCSE, as well as a new strategy outlining how education will be used to improve knowledge of climate change and sustainability (DfE, 2022). Communication, more generally, is appearing through the mainstream media (Boykoff and Luedecke, 2016) and lifelong education— for example, Carbon Literacy training (Chapple et al., 2020) or Climate Fresk (Leimbach and Milstein, 2022), delivering climate messaging to the wider population; not just those in formal education. Implementation of these CCE strategies is promising and could prove important in improving climate literacy.

Systematic reviews of CCE strategies have been undertaken, which identified common approaches in teaching about the topic, for example through addressing misconceptions, use of scientific knowledge and student participation (Kagawa and Selby, 2010; Monroe et al., 2019; Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020). However, arguments have arisen which see education as largely about, rather than for or in the environment(Dunlop and Rushton, 2022; Glackin and King, 2020), highlighting that more work needs to be done on its framing and values.

2.2 The danger of climate anxiety

Ensuring CCE strategies are effective is important in empowering individuals to act. However, exposure to negative information can cause distress and, in some cases, climate anxiety (Whitmarsh et al., 2022). Climate anxiety is a relatively novel phenomena, with varying definitions. Its conceptualisation largely stems from eco-anxiety, defined as ‘a chronic fear of environmental doom’ (Clayton et al., 2017, p.68) and can create tangible symptoms (see Table 1). However, some make calls to not pathologise climate anxiety and instead view it as a useful call-to-action (Dodds, 2021; Lawton, 2019). Yet, Hickman (2020) warns us not to create a concrete definition for climate anxiety, and instead to explore the various ways of framing emotions surrounding climate change. By understanding how people react to climate change, their sometimes-difficult emotions can be validated (Kennedy-Woodard and Kennedy-Williams, 2022), rather than dismissing them as “normal” — something encouraged with other forms of mental ill health (Shahar, 2020).

| Severe symptoms | Mild symptoms |

| Significant psychosomatic symptoms: serious insomnia, states of depression, clinically | Occasional insomnia |

| Definable anxiety (“Climate Anxiety Disorder”) | Sadness, restlessness (milder symptoms of anxiety) |

| Difficulty maintaining functioning, especially when faced with news about climate change its consequences and threat scenarios | Occasional decreased levels of functioning, temporary paralysis, for example, when making moral decisions |

| Compulsive behaviour, this includes behaviours that have been called “climate anorexia” or “climate orthorexia” | Effects on mood |

| Self-destructive behaviours, for example, substance abuse and self-harming | Milder symptomatic behaviour, for example, single action bias or mild dissociation |

Table 1: climate anxiety symptoms (adapted from Pihkala, 2019)

Drawing from Table 1, a range of climate anxiety symptoms could be experienced. In some cases, climate anxiety can be disabling and have serious consequences on an individual’s quality of life (Ojala et al., 2021). Additionally, symptoms can create fatalism or be debilitating, reducing a person’s ability to take effective action (“eco-paralysis”) (Heeren, Mouguiama-Daouda and Contreras, 2022). Studies have begun to quantify how many people are experiencing climate anxiety. In the UK, 43% of adults identified as ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ anxious about climate change (ONS, 2021). Young people are also anxious, with 45% of respondents in a global survey believing their anxieties surrounding climate change had an impact on everyday life, largely caused by feelings of government betrayal (Hickman et al., 2021). Therefore, climate change educators need to take steps to safeguard individuals’ wellbeing. With the vast impacts of climate change (IPCC, 2018), clearly this education needs to instil urgency, to inspire prompt and meaningful action. However, striking a balance between this urgency, whilst being mindful of individuals’ capacity to cope, is important to ensure resilience in the face of crisis.

3. How to effectively educate about climate change

Educators need to be comfortable with inspiring action, whilst reducing possible contributions to climate anxiety. To this end, three potential strategies are presented, which educators could adopt: solutions-based teaching, generating hope and embracing uncertainty. Each strategy was chosen with three criteria in mind: any educator could implement it; it has previously generated tangible results, and it combines reducing anxiety with empowering action.

3.1 Solutions-based teaching

Climate change is seen as a major problem, with myriad contributing factors (IPCC, 2018). Many report feeling guilty about their contribution, for instance due to personal-consumption habits (Ágoston et al., 2022). Presenting climate change as a large-scale problem can seem daunting and can contribute towards psychological paralysis (Innocenti et al., 2023). Anxiety involves rumination, and action is often suggested to be the best antidote for breaking these cycles (Fyke and Weaver, 2023; Ray, 2020). Therefore, balancing out problems, with corresponding solutions, enables individuals to feel as if they can make a difference, even if small. A particular way of embedding solutions-based education is to view problems through a localised lens. The success of such an approach can be seen through the Institute for Humane Learning’s project-based learning scheme, where educators support students in examining a local problem, and envisioning solutions which could be applied. For instance, manipulating climate data to see the impacts of climate change on their area, and discussing potential solutions (Schwartz, 2021). Not only does this develop interpersonal skills, such as teamwork and communication, but also allows for a sense of fulfilment, reducing climate anxiety (Bell, 2010).

3.2 Generating hope

Climate change, presented in a futile way, can lead to fatalism, whereby individuals believe their actions have no meaningful impact. This can contribute to climate anxiety, due to lack of hope (Taylor, 2023). In a study by Hickman et al. (2021) of young people, they found two-thirds of respondents felt unoptimistic about climate change. This was higher in the UK, with 71.1% of respondents feeling unoptimistic. Therefore, it is important to inspire hope. Despite the existence of viable pathways to a sustainable future, they aren’t always highlighted (Rogelj et al., 2018; Ojala, 2015). When educating about climate change, there are emotional elements to discussions, and room should be left for these. By working through emotions and creating trust and honesty amongst peers, individuals may feel more optimistic (Swim and Fraser, 2013). This can be achieved through making the learning environment a safe space, by setting ground rules for discussion, as well as encouraging honesty and transparency in learning (Ray, 2020). Hope is also positively linked to action competence (Finnegan, 2023). Therefore, linking solutions-based learning, action and emotional mediation could lead to hope, thereby reducing levels of climate anxiety.

3.3 Embracing uncertainty

Climate change has been politicised, with the science behind discussions becoming increasingly scrutinised (Okereke, Wittneben and Bowen, 2012). Climate science is a relatively new field of study. Therefore, understandably, there are uncertainties and disagreements (Curry and Webster, 2011). The media, which is a prolific source of climate change information, has played a part in creating uncertainty (Painter, 2016). For example, climate scientist Tamsin Edwards (2014) recalls a paper about the effects of flooding on London being reported in different ways. On one website it was reported that flooding would be more severe than initially predicted, whilst on another site it was less severe. This was due to contrasting perspectives of the media when comparing this article with previous studies. Humans naturally dislike uncertainty, as it can make us fearful (Carleton, 2016). Denial is a natural response in dealing with uncertainty, as it allows us to avoid confronting the truth (Friedrichs, 2014). In the case of climate change, anxiety and uncertainty could reduce a person’s willingness to act, as they avoid confronting difficult emotions. By acknowledging that it is normal to experience uncertainty about climate change, we can create richer discussions and help individuals to reach their own, informed conclusions, rather than dismissing climate change to avoid doubt and anxiety.

Moreover, individuals need to be able to accept the notion of a climate-altered world. Despite adaptation and mitigation efforts, climate change has and continues to affect people and planet (IPCC, 2018). In discussions with her students, Ray (2020) found that some could not imagine what the world will be like following climate change. The Paris Agreement of keeping temperature increases below 2°C is sometimes presented as the be-all-and-end-all, and that the world would suddenly end if we crossed this threshold (Marris, 2023). Whilst the impacts will be significant, this is false, and life will continue (Thunberg, 2022). We need, therefore, to foster hope, and empower individuals to think about what a climate-altered future will look like. For instance, a video produced by Naomi Klein tells the story of an alternate future, following COVID-19, that saw ecological and social repair, for a fairer and more sustainable society (Boekbinder and Batt, 2020). Resources like this can be used to inspire individuals to use climate change as a catalyst for a better future.

4. Conclusion

Climate change is a significant global issue, which requires cross-societal cooperation. Understanding what climate change is, its effects, and how we can reduce our individual and collective contributions, will be vital in creating a more sustainable and just world. Education is one of the most important tools we have in raising awareness of the climate crisis, but ensuring it prompts action, rather than anxiety, is important in ensuring individuals have the continued resilience required to tackle this tough challenge. By focussing on solutions, instilling hope, and accepting uncertainty (and the synergies between these strategies), unnecessary stress on individuals can be reduced. Instead, their emotional energy can be directed towards meaningful action to reharmonise people and planet.

Acknowledgements

My grateful thanks go to Lynda Dunlop for running an engaging and inspiring module that sparked my interest in the relationship between education and the environment, as well as for reviewing drafts of this paper. I am indebted to Katherine Brookfield for supervising the project which laid the groundwork for this paper. Thanks also to Michelle Graffagnino and Nicola Warren-Lee for challenging me to think deeply and question more.

References

Ágoston, C., Csaba, B., Nagy, B., Kőváry, Z., Dúll, A., Rácz, J. and Demetrovics, Z. (2022). Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 2461.

Arango, C., Díaz-Caneja, C., McGorry, P.D., Rapoport, J. Sommer, I.E., Vorstman, J.A., McDaid, D., Marín, O., Serrano-Drozdowskyj, E., Freedman, R., Carpenter, W. (2018). Preventive strategies for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(7), 591-604.

Armstrong McKay, D.I., Staal, A., Abrams, J.F., Winkelmann, R., Sakschewski, B., Loriani, S., Fetzer, I., Cornell, S.E., Rockström, J. and Lenton, T.M. (2022). Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science, 377, 1171.

Bell, S. (2010). Project-Based Learning for the 21st Century: Skills for the Future. The Clearing House, 83(2), 39-43.

Boekbinder, K. and Batt, J. (Directors). (2020). A Message from the Future II: The Years of Repair. [Film]. New York: The Intercept.

Boykoff, M. and Luedecke, G. (2016). Elite News Coverage of Climate Change. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brondizio, E., Diaz, S., Settele, J. and Ngo, H.T. (Eds.). (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES.

Carleton, R.N. (2016). Into the unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 39(April 2016), 30-43.

Caroll, J.G. and Winship, W.E. (2019). Ahead of Its Time: The Early Twentieth Century Electric Vehicle. Moosic: Endless Mountains Publishing.

Chapple, W., Molthan-Hill, P., Welton, R. and Hewitt, M. (2019). Lights Off, Spot On: Carbon Literacy Training Crossing Boundaries in the Television Industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 162, 813-834.

Clayton, S. and Karazsia, B.T. (2020). Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69(June 2020), 101434.

Clayton, S., Manning, C., Krygsman, K. and Speiser, M. (2017). Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance. Washington, D.C.: APA.

Cologna, V. and Siegrist, M. (2020). The role of trust for climate change mitigation and adaptation behaviour: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69, 101428.

Curry, J.A. and Webster, P.J. (2011). Climate Science and the Uncertainty Monster. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 92(12), 1667-1682.

Department for Education (DfE). (2022). Sustainability and climate change: a strategy for the education and children’s services systems. London: Department for Education.

Dodds, J. (2021). The psychology of climate anxiety. BJPsych Bulletin, 45(4), pp.222-226.

Dunlop, L. and Rushton, E.A.C. (2022). Putting climate change at the heart of education: Is England’s strategy a placebo for policy? British Educational Research Journal, 48(6), 1083-1101.

Edwards, T. (2014). How to love uncertainty in climate science. [Video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RP5nhmp06xs&ab_channel=TEDxTalks [Accessed 2 June 2023].

Finnegan, W. (2023) Educating for hope and action competence: a study of secondary school students and teachers in England. Environmental Education Research, 29(11), 1617-1636.

Frick, M., Neu, L., Liebhaber, N., Sperner-Unterweger, B., Stötter, J., Keller, L., Hüfner, K. (2021). Why Do We Harm the Environment or Our Personal Health despite Better Knowledge? The Knowledge Action Gap in Healthy and Climate-Friendly Behavior. Sustainability, 13(23), 13361.

Friedrichs, J. (2014). Useful lies: The twisted rationality of denial. Philosophical Psychology, 27(2), 212-234.

Fyke, J. and Weaver, A. (2023). Reducing personal climate risk to reduce personal climate anxiety. Nature Climate Change, 13, 209-210.

Glackin, M. and King, H. (2020). Taking stock of environmental education policy in England – the what, the where and the why. Environmental Education Research, 26(3), 305-323.

Gutteres, A. (2021). Secretary-General’s statement on the IPCC Working Group 1 Report on the Physical Science Basis of the Sixth Assessment [Online]. United Nations. Last updated: 9 August 2021. Available at: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/secretary-generals-statement-the-ipcc-working-group-1-report-the-physical-science-basis-of-the-sixth-assessment. [Accessed 5 April 2023].

Haddaway, N. R., and Duggan, J. (2023). ‘Safe spaces’ and community building for climate scientists, exploring emotions through a case study. Global Environmental Psychology, 1, e11347.

Heeren, A., Mouguiama-Daouda, C. and Contreras, A. (2022). On climate anxiety and the threat it may pose to daily life functioning and adaptation: a study among European and African French-speaking participants. Climatic Change, 173, 15.

Herr, A.Z. (2022). Narratives of Hope: Imagination and Alternative Futures in Climate Change Literature. Transcience, 13(2), 88-111.

Hickman, C. (2020). We need to (find a way to) talk about … Eco-anxiety. Journal of Social Work Practice, 34(4), 411-424.

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R., Mayall, E., Wray, B., Mellor, C. and van Susteren, L. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(12), e863-e873.

Hornsey, M.J. and Fielding, K.S. (2016). A cautionary note about messages of hope: Focusing on progress in reducing carbon emissions weakens mitigation motivation. Global Environmental Change, 39, 26-34.

Inayatullah, S. (2008). Six pillars: futures thinking for transforming. Foresight, 10(1), 4-21.

Innocenti, M., Santarelli, G., Lombardi, G.S., Ciabini, L., Zjalic, D., Di Russo, M. and Cadeddu, C. (2023). How Can Climate Change Anxiety Induce Both Pro-Environmental Behaviours and Eco-Paralysis? The Mediating Role of General Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20, 3085.

IPCC. (2018). Impacts of 1.5°C of Global Warming on Natural and Human Systems. Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Geneva: IPCC.

Jensen, B. and Schnack, K. (1997). The action competence approach in environmental

education. Environmental Education Research, 3(2), 163-178.

Kennedy-Woodard, M. and Kennedy-Williams, P., 2022. Turn the tide on climate anxiety. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Kirby, P. and Webb, R. (Eds.). (2023). Creating with uncertainty: Sustainability education resources for a changing world. Brighton: University of Sussex.

Larionow, P., Sołtys, M., Izdebski, P., Mudło-Głagolska, K., Golonka, J., Demski, M. and Rosińska, M., 2022. Climate Change Anxiety Assessment: The Psychometric Properties of the Polish Version of the Climate Anxiety Scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 870392.

Lawton, G. (2019). If we label eco-anxiety as an illness, climate denialists have won. London: New Scientist.

Leimbach, T. and Milstein, T. (2022). Learning to change: Climate action pedagogy. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 62(3), 414-423.

Li, C.J. and Monroe, M.C. (2017). Exploring the essential psychological factors in fostering hope concerning climate change. Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 936-954.

Manzanedo, R.D. and Manning, P. (2020). COVID-19: Lessons for the climate change emergency. Science of The Total Environment, 742, 140563.

Marris, E. (2023).1.5 Degrees Was Never the End of the World. [Online]. The Atlantic. Last updated: 1 February 2023. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2023/02/climate-change-paris-agreement-15-degrees-celsius-goal/672909/ [Accessed 7 June 2023].

Matulka, R. (2014). The history of the electric car. [Online]. Department for Energy. Last updated: 15 September 2014. Available at: https://www.energy.gov/articles/history-electric-car [Accessed 19 April 2024].

Miléř, T. and Sládeka, P. (2011). The climate literacy challenge. International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology 2010. 150-156.

Monroe, M. C., Plate, R. R., Oxarart, A., Bowers, A., and Chaves, W. A. (2019). Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the research. Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 791–812.

Nerlich, B., Koteyko, N. and Brown, B. (2009). Theory and language of climate change communication. WIREs Climate Change, 1(1), 97-110.

Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2021). Opinions and Lifestyle Survey. Data on public attitudes to the environment and the impact of climate change, Great Britain. [Online]. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/datasets/dataonpublicattitudestotheenvironmentandtheimpactofclimatechangegreatbritain. [Accessed 21 June 2022].

Ojala, M. (2015). Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Associations With Environmental Engagement and Student Perceptions of Teachers’ Emotion Communication Style and Future Orientation. The Journal of Environmental Education, 46(3), 133-148.

Ojala, M. (2023). Hope and climate-change engagement from a psychological perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 49, 101514.

Ojala, M., Cunsolo, A., Ogunbode, C.A. and Middleton, J. (2021). Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 46, 35-58.

Okereke, C., Wittneben, B. and Bowen, F. (2012). Climate Change: Challenging Business,

Transforming Politics. Business & Society, 51(1), 7-30.

Painter, J. (2016). Journalistic Depictions of Uncertainty about Climate Change. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pedde, S., Kok, K., Hölscher, K., Frantzeskaki, N., Holman, I., Dunford, R., Smith A. and Jäger, J. (2019). Advancing the use of scenarios to understand society’s capacity to achieve the 1.5 degree target. Global Environmental Change, 56(May 2019), 75-85.

Pihkala, P. (2019). Climate Anxiety. Helsinki: MIELI Mental Health Finland.

Pihkala, P. (2020). Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability, 12, 7836.

Ray, S. (2020). A field guide to climate anxiety. Oakland: California University Press.

Rogelj, J., D. Shindell, K. Jiang, S. Fifita, P. Forster, V. Ginzburg, C. Handa, H. Kheshgi, S. Kobayashi, E. Kriegler, L. Mundaca, R. Séférian, and M.V.Vilariño. (2018). Mitigation Pathways Compatible with 1.5°C in the Context of Sustainable Development. In: V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (Eds.). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 93-174.

Rousell, D and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A. (2020). A systematic review of climate change education: giving children and young people a ‘voice’ and a ‘hand’ in redressing climate change. Children’s Geographies, 18(2), 191–208.

Selby, D. and Kagawa, F. (2010). Runaway climate change as challenge to the ‘closing circle’ of education for sustainable development. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 4(1), 37–50.

Schwartz, S. (2021). Finding Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Why Some Teachers Focus on Solutions [Online]. EducationWeek. Last updated: 23 November 2021. Available at: https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/finding-hope-in-the-face-of-climate-change-why-some-teachers-focus-on-solutions/2021/11 [Accessed 15 April 2023].

Shahar, B. (2020). New Developments in Emotion-Focused Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9, 2918.

Simpson, N.P., Andrews, T.M., Krönke, M., Lennard, C., Odoulami, R.C., Ouweneel, B., Steynor, A. and Trisos, C.H. (2021). Climate change literacy in Africa. Nature Climate Change, 11, 937-944.

Swim, J.K. and Fraser, J. (2013). Fostering Hope in Climate Change Educators. Journal of Museum Education, 38(3), 286-297.

Taylor, D. (2023). Climate anxiety, fatalism and the capacity to act. In Watkin, C. and Davis, O.. (Eds.). New Interdisciplinary Perspectives On and Beyond Autonomy. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 150-164.

Tauritz, R.L. (2012 How to handle knowledge uncertainty: learning and teaching in times of accelerating change. In Wals, A.E.J. and Corcoran, P.B. (Eds). Learning for sustainability in times of accelerating change. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers, pp. 297–316.

Thunberg, G. (2022). The Climate Book. London: Allen Lane.

United Nations (UN). (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). (2022). Matters relating to Action for Climate Empowerment (6-12 August 2023). [Online]. FCCC/SBI/2022/L.23. [Accessed 6 April 2023]. Available from: https://unfccc.int/event/sbi-57?item=22.

Vazard, J. (2024). Feeling the Unknown: Emotions of Uncertainty and Their Valence. Erkenn 89, 1275–1294.

Whitmarsh, L., Player, L., Jiongco, A., James, M., Williams, M., Marks, E. and Kennedy-Williams, P. (2022). Climate anxiety: What predicts it and how is it related to climate action? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 83(October 2022), 101866.

#Write for Routes

Are you 6th form or undergraduate geographer?

Do you have work that you are proud of and want to share?

Submit your work to our expert team of peer reviewers who will help you take it to the next level.

Related articles