Volume 4 Issue 3

By Alice Read-Clarke, Queen Anne’s School

Citation

Read-Clarke, A. 2025. Marine Protected Areas: How effective are they at protecting marine ecosystems? Routes, 4(3): 218-227.

Abstract

Marine Protected Areas are a conservation method frequently implemented by governments with the intention of ensuring the health of marine ecosystems. This essay investigates the impact of Marine Protected Areas on marine ecosystems, specifically the flora and fauna, as well as the limitations which affect the ability of Marine Protected Areas to protect these ecosystems. This essay uses case studies of Marine Protected Areas across different scales from across the globe. Based on these case studies, this essay concludes that, whilst Marine Protected Areas are very effective in protecting marine ecosystems, they must be carefully balanced against the social and economic impacts of their implementation. They can increase coral cover, protect and restore the population of marine mammals, and increase the biomass in the protected area. However, the political motivations which underpin the creation of Marine Protected Areas can impact on their efficacy.

1. Introduction

Marine ecosystems are at risk from a variety of stressors, most notably climate change, alongside the impacts of an increasing population which relies on the sea. Activities including mining, fishing, tourism, and transport can all have detrimental effects on marine fauna and flora, as well as on abiotic factors, specifically sea temperature and water acidity. However, action has been, and is being, taken in order to protect unique, fragile, and vital marine ecosystems from the impact of both humans and climate change.

The creation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) aims to reduce the impact of human activity, conserve marine habitats, and increase biodiversity. MPAs are a ‘clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated, and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values’ (Joint Nature Conservation Committee, 2023). There are many classifications of MPA; there are four stages of establishment, four levels of protection, four types of enabling conditions and four different outcomes (The MPA Guide, 2023). MPAs can also be classified as small scale, covering an area less than 150,000 km2 such as the Gili Matra Marine Tourism Park in Indonesia, or large scale, covering an area greater than 150,000 km2 such as the Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area in Antarctica and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia.

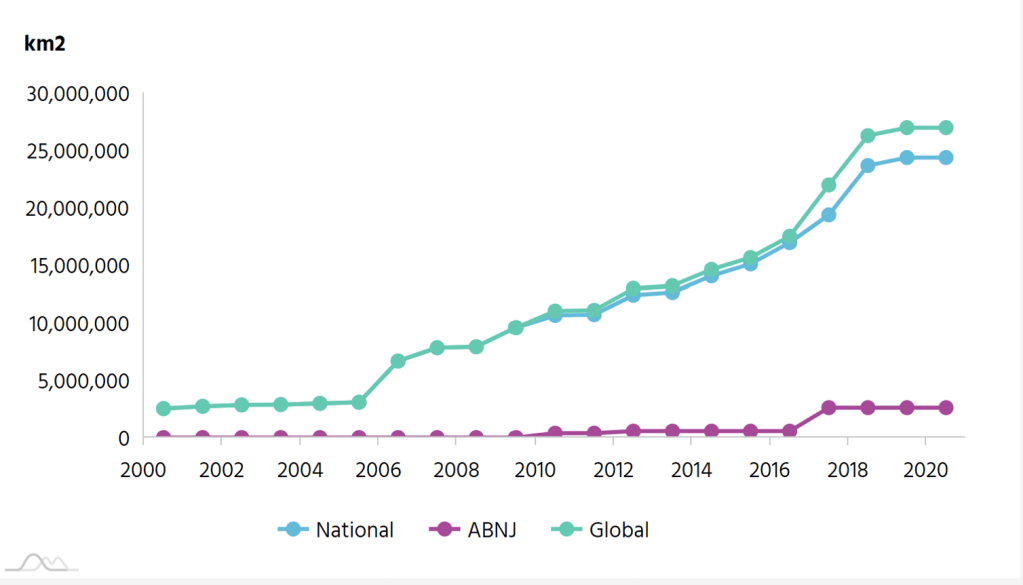

It is important to investigate the effectiveness of MPAs as a conservation strategy as the area of ocean protected under these has increased rapidly since 2006. As shown by Figure 1, global ocean coverage by MPA’s has increased tenfold. More recently there has also been an increase seen in the amount of area protected in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), which is projected to increase with the introduction of a number of MPA’s proposed under the High Seas Treaty, signed in 2023 (High Seas Alliance, n.d.). This essay will contribute to the growing body of literature on the effectiveness of MPAs, giving a clear overview of their impact in a variety of situations and what lessons can be learned for future projects.

Figure 1: Graph of MPA coverage growth CITATION Pro24 \l 2057 (Protected Planet, n.d.)

This essay will consider a number of case studies in order to assess the general effectiveness of Marine Protected Areas. The Ross Sea MPA and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park are useful case studies as they are both long established, large-scale MPA’s with a large amount of research conducted on their effectiveness. The Ross Sea MPA is also an important study in protecting oceans which are ABNJ. The Gili Matra MPA is a case study which demonstrates a project that has aimed to find balance between tourism and economic activity, and environmental protection, and so it is important to assess if this has been achieved. There is one source included in this paper which was published more than 10 years ago, and is used as it relates to a historical event of pollution within an MPA.

Marine Protected Areas can increase the total marine biomass in an area, allow marine species to recover from environmental change and conserve sensitive marine habitats such as coral reefs. Despite the ecological benefits of MPAsthere are issues with their implementation and effectiveness that reduce their potential to conserve marine ecosystems. The main causes of MPA failure are social, political, and economic challenges, alongside physical factors.

2. The impact of Marine Protected Areas on marine ecosystems

MPAs, when implemented well, have a multitude of positive impacts on marine ecosystems. A study published in 2009 shows that, in no-take marine reserves (an area in which no extractive activities are allowed), there is on average a positive effect on the biomass, numerical density, species variety, and size of organisms found in the protected area (Lester, et al., 2009). Whilethis study focused onno-take reserves in both temperate and tropical climates, its narrow focus on onlyno-take reserves does not evaluate whether MPAs with lower levels of protection are as effective at increasing biodiversity and the health of marine populations. However, there is evidence to suggest that well-protected MPAs, combined with sustainable fisheries adjacent to the MPA, can actually increase fishery catches (Sala and Giakoumi, 2017). This suggests that a carefully controlled combination of protection and extraction can allow marine species to prosper.

2.1. Marine mammals

MPAs also help to protect marine mammals, although this is more complex than the use of MPAs to protect smaller marine animals. Large marine mammals, for example whales and dolphins, are considered marine highly mobile species (MHMS), meaning that they travel long distances. Despite the efforts of MPAs, for example the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area, which explicitly cites the protection of large marine mammals as a key driver for its establishment (Conners, et al., 2022), it remains difficult to protect these creatures within a specified area. However, it has been demonstrated that MPAs are effective in protecting MHMS when they are located in the habitats which are critical to the survival of the species (Tomas & Sanabria, 2022). One example of this is the increasing population of the Hawaiian humpback whale, whose critical breeding habitat in Hawaii is protected. Their population increased so drastically that they were delisted as an endangered species in 2016 (Tomas & Sanabria, 2022).

2.2. Coral

Lastly, the creation of MPAs and local ecosystem management also has the potential to increase coral cover, specifical of juvenile corals (Steneck et al., 2018). Coral is a vital habitat for marine creatures, as well as providing benefits for people as a source of income and protection against coastal erosion (Natural History Museum, n.d.). Strain et al. (2018) studied 30 MPA’s, establishing that they were most effective at conserving high levels of coral cover when they were well-enforced, no-take and had been established for longer than 10 years. Of these, the most important is that the area is well enforced and no-take, with these having 1.17x and 1.19x more total coral cover respectively, than other MPAs which are not well enforced and fished. The size of the MPA has no clear influence on coral cover (Strain, et al., 2018). Whilst MPAs protect coral populations from localised impacts, they are unlikely to protect them from regional and global stressors such as climate change, which can lead to mass coral bleaching (Johnson, Dick and Pincheira-Donoso, 2022). Coral has been severely affected in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, where it has experienced massive coral bleaching and death (Pendleton, et al., 2018; Johnson, Dick and Pincheira-Donoso, 2022), primarily caused by heat stress from raised water temperatures (Great Barrier Reef Foundation, 2023; Johnson, Dick and Pincheira-Donoso, 2022). The prevalence of coral bleaching is similar in areas of coral covered by MPAs and areas not protected (Johnson, Dick and Pincheira-Donoso, 2022). Overall, marine protected areas, when well-managed, have been shown to conserve and even improve the health and resilience of marine ecosystems and marine animal populations.

3. Limitations of Marine Protected Areas

However great the potential of MPAs to improve marine ecosystems, there are multiple reasons why they are not always an effective measure. The criticisms of MPAs can be split into two main categories; physical issues – including size, influence of unprotected surrounding ecosystems, and the inability to protect areas from large scale events – and social, economic, and political issues – including poor management, the designation of ‘paper parks’ for political reasons, and conflict as a result of reduced opportunity for economic activities including tourism and fishing.

3.1. Size

MPAs can fail as a result of either being too small or too large. MPAs which are too small can fail to adequately protect the large area in which most marine animals live (Bonnin et al., 2021). However, large scale MPAs (LSMPAs) are not necessarily more effective than smaller ones. LSMPAs are generally better at protecting migratory species and marine wildernesses as well as fortifying marine ecosystems to survive large-scale and long-term disturbances including climate change, pollution, and ocean acidification. However, there is concern that the coverage of LSMPAs in order to meet politically motivated conservation goals, such as protecting a percentage of a country’s ocean area, is being prioritised over their ability to protect marine environments (Artis, et al., 2020). It is also debated whether LSMPAs can be effectively monitored and enforced, due to their large size, often remote location, and their zonal usage (Artis, et al., 2020). Zoned usage means that an MPA is split into zones where different levels and types of activity are allowed. This occurs most often in LSMPAs and means that, while one area of the LSMPA may be a no-take area, another area may allow some types of minorly intrusive fishing. This makes enforcement and monitoring more difficult as it becomes harder to ensure that the relevant rules are being followed. Although LSMPAs have a greater potential than MPAs to protect marine environments from global stressors, it is clear that no one tool can be effective on its own (O’Leary, et al., 2018).

3.2. External factors

Despite protecting marine ecosystems, MPAs can be ineffective at preventing the impact of pollution from elsewhere, specifically human activities on the land, which subsequently degrades the marine ecosystem which MPAs aim to conserve. For example, in the early days of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP), some areas of the reef experienced eutrophication and algal overgrowth as a result of fertiliser runoff from sugar cane production in Queensland (Agardy, et al., 2010). Even though this problem has since been rectified, there are other MPAs which have not been able to protect ecosystems from factors outside their range of protection. One example of this is the Buck Island National Park in the US Virgin Islands. One of the most important species that this park was established to protect was the elkhorn coral. Today virtually all of the elkhorn coral in this area is dead as a result of widespread white band disease in the 1980’s which reduced coral cover by over 90% (Ewen, 2022). Whilst there are other actions which can be taken to prevent human created incidents that negatively affect marine ecosystems, including reducing pollution and mitigating the impact of climate change induced weather events, from having negative impacts on marine ecosystems, it is much harder to prevent the impacts of naturally occurring events such as diseases. These instances exemplify the fact that MPAs, whilst helpful, cannot be used as a single resource to protect marine ecosystems.

3.3. Political limitations

When MPAs are ineffectively enforced they can become ‘paper parks,’ which are MPAs which are officially designated but ineffective at meeting their goals (Relano & Pauly, 2023). There are many reasons why MPAs may be ineffective at meeting their goals. One significant reason is unclear categorisation of the MPA which leads to approaches that are not specific enough to protect the marine ecosystems. Therefore, this can result in MPAs being misclassified which leads to ill-defined conservation goals and confusion about the intended level of protection (Relano & Pauly, 2023). This can also reduce public and political confidence in the use of MPAs. A lack of stakeholder engagement is also considered a main driver of MPA failure (Giakoumi, et al., 2018). It is important that stakeholders, especially those whose compliance is crucial to MPA effectiveness, are involved in the process of establishing and enforcing MPAs (Giakoumi, et al., 2018). For this reason, it is generally easier to establish MPAs in remote areas, where there are fewer direct stakeholders (O’Leary, et al., 2018), however this can often be seen governments attempting to fulfil conservation quotas whilst not enforcing actual protection. Some argue that it is more effective to pre-emptively protect less affected areas, usually those which are more remote, and use marine spatial planning and zoned multiple-use LSMPAs in areas which have a higher number of human uses (O’Leary, et al., 2018). This can also help to reduce conflict with local people as it minimises the effects of MPAs on social and economic activities.

3.4. Social and economic impacts

In order to ensure maximum compliance with the rules of an MPA, it is important to consider the economic and social impacts on the surrounding communities and to ensure there are provisions in place to minimise the negative impacts. One example of an MPA where this is an established practice is the Gili Matra Marine Tourism Park (Gili Matra MPA) in Indonesia. The conservation targets of the Gili Matra MPA are two-fold; the preservation of essential marine ecosystems such as coral reefs, mangroves, seagrasses, and fishery resources, combined with the supporting local communities, fishers, and tourism operators (Rosadi, et al., 2022). The Gili Matra MPA’s combined targets of ecological conservation along with social and economic preservation have boosted ecotourism, however there is still some conflict emerging from the fact that the MPA is managed with a top-down, rather than a bottom-up, approach (Rosadi, et al., 2022). This can be facilitated by the involvement of NGOs in the process of establishing MPA’s, as they can act as a bridging organisation between the government and local stakeholders, as well as providing training, a diverse knowledge base and access to physical and financial resources (White et al., 2022).

4. Conclusion

Overall, Marine Protected Areas have immense potential for conserving marine ecosystems; increasing levels of biodiversity and biomass, improving the health and resilience of the marine ecosystem, and when carefully located, increasing the viability of populations of MHMS. However, MPAs can only be effective in conserving marine ecosystems when there is also careful consideration of the economic and social impacts of their establishment; stakeholder involvement is particularly important in ensuring that local communities understand and comply with the rules of a designated MPA. Furthermore, MPAs require close monitoring to ensure that they are meeting conservation goals and are to prevent them becoming ‘paper parks.’ Finally, it is important that MPAs are not seen as the sole measure capable of protecting marine ecosystems, and that wider action is taken to reduce the impacts of human caused climate change, and pollution on the marine ecosystem being protected.

This essay lays out the clear evidence that MPA’s are a highly effective tool in the conservation of marine ecosystems. However, their effectiveness can be limited by issues with political decision making, size and external factors. If they are to be used as a tool in sustainable development, then they must balance environmental conservation with the rights and interests of stakeholders, particularly local and indigenous peoples. The findings of this essay make it clear that further research is required to understand what best practice is when including local stakeholders in MPA’s creation and maintenance. It is also clear that this should be done on a proposal-by-proposal basis, as each case is so different and has many different factors affecting it.

References

Agardy, T., Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. & Christie, P., 2010. Mind the gap: Addressing the shortcoming of marine protected areas through large scale marine spatial planning. Elsevier.

Artis, E. et al., 2020. Stakeholder perspectives on large-scale marine protected areas. PLoS One.

Bonnin, L., Mouillot, D., Boussarie, G., Robbins, W.D., Kiszka, J.J., Dargorn, L. and Vigliola, L. (2021). Recent expansion of marine protected areas matches with home range of grey reef sharks. Scientific Reports, [online] 11. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-93426-y [Accessed 6 Nov. 2024]

Conners, M. et al., 2022. Mismatches in scale between highly mobile marine megafauna and marine protected areas. Frontiers in Marine Science.

Ewen, K.A. 2022. Buck Island’s Corals Get Relief from a Deadly Disease (U.S. National Park Service). [online] http://www.nps.gov. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/buck-islands-corals-get-relief-from-a-deadly-disease.htm [Accessed 6 Nov. 2024].

Giakoumi, S. et al., 2018. Revisiting “Success” and “Failure” of Marine Protected Areas: A Conservation Scientist Perspective. Frontiers in Marine Science.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation, 2023. Coral Bleaching. [Online] Available at: https://www.barrierreef.org/the-reef/threats/coral-bleaching#:~:text=A%20primary%20cause%20of%20coral,four%20weeks%20can%20trigger%20bleaching

High Seas Alliance, n.d. A momentous milestone for the ocean and global biodiversity. [Online] Available at: https://www.highseasalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/HSA_Treaty_Factsheet_27June23.pdf [Accessed 19 July 2024].

Johnson, J.V., Dick, J.T.A. and Pincheira-Donoso, D. 2022. Marine protected areas do not buffer corals from bleaching under global warming. BMC Ecology and Evolution, [online] 22. Available at: https://bmcecolevol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12862-022-02011-y [Accessed 6 Nov. 2024].

Joint Nature Conservation Committee, 2023. About Marine Protected Areas. [Online]

Available at: https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/about-marine-protected-areas/.

Lester, S. E. et al., 2009. Biological effects within no-take marine reserves: a global synthesis, s.l.: Inter-Research.

Natural History Museum, n.d. Why are coral reefs so important?. [Online] Available at: https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/quick-questions/why-are-coral-reefs-important.html.

O’Leary, B. C. et al., 2018. Addressing Criticisms of Large-Scale Marine Protected Areas. BioScience, pp. 359-370.

Pendleton, L. H. et al., 2018. Debating the effectiveness of marine protected areas. ICES Journal of Marine Science, pp. 1156-1159.

Protected Planet, n.d. Marine Protected Areas. [Online] Available at: https://www.protectedplanet.net/en/thematic-areas/marine-protected-areas#:~:text=Growth%20in%20marine%20protected%20area%20coverage,-Over%20the%20last&text=In%202000%20the%20area%20covered,ocean%20being%20covered%20by%20MPAs. [Accessed 19 July 2024].

Relano, V. & Pauly, D., 2023. The ‘Paper Park Index’: Evaluation Marine Protected Area effectiveness through a global study of stakeholder perceptions. Elsevier.

Rosadi, A., Dargusch, P. & Taryono, T., 2022. Understanding How Marine Protected Areas Influence Local Prosperity – A Case Study of Gili Matra, Indonesia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Sala, E. and Giakoumi, S. 2017. No-take marine reserves are the most effective protected areas in the ocean. ICES Journal of Marine Science, [online] 75(3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsx059 [Accessed 6 Nov. 2024].

Steneck, R.S., Mumby, P.J., MacDonald, C., Rasher, D.B. and Stoyle, G. 2018. Attenuating effects of ecosystem management on coral reefs. Science Advances, [online] 4(5). doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aao5493.

Strain, E. M. A. et al., 2018. A global assessment of the direct and indirect benefits of marine protected areas for coral reef conservation. Diversity and Distributions, pp. 9-20.

The MPA Guide, 2023. The MPA Guide. [Online] Available at: https://mpa-guide.protectedplanet.net/.

Tomas, E. G. & Sanabria, J. G., 2022. Comparative analysis of marine-protected area effectiveness in the protection of marine mammals: Lessons learned and recommendations. Frontiers in Marine Science, 24 November.

vitae, 2023. Reseach Project Stakeholders. [Online] Available at: https://www.vitae.ac.uk/doing-research/leadership-development-for-principal-investigators-pis/leading-a-research-project/applying-for-research-funding/research-project-stakeholders#:~:text=Stakeholders%20are%20people%20or%20organisations,or%20indeed%20cri.

White, C.M., Mangubhai, S., Rumetna, L. and Brooks, C.M. 2022. The bridging role of non-governmental organization in the planning, adoption, and management of the marine protected area network in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. Marine Policy, [online] 141. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105095. [Accessed 6 Nov. 2024].

#Write for Routes

Are you 6th form or undergraduate geographer?

Do you have work that you are proud of and want to share?

Submit your work to our expert team of peer reviewers who will help you take it to the next level.

Related articles