Volume 5 Issue 1

By Hannah Taylor, The Grammar School at Leeds & Durham University

Citation

Taylor, H. 2026. The ‘demographic timebomb’: a ticking clock, or has it detonated already? Routes, 5(1): 5-16.

Abstract

This essay examines the narrative of the ‘demographic timebomb’ by exploring the causes, consequences, and policy responses to global population ageing. Using case studies of different regions, it considers both the economic risks often highlighted in ageing societies while recognising the significant economic, social and cultural contributions made by older adults. The analysis advocates for long-term strategies including increasing the pension age, investing in human capital, designing cohesive migration strategies, embracing technological advances and supporting families. It concludes that through proactive policy interventions and a multifaceted approach that enables people to make a positive contribution to society and helps support workforce participation and productivity, countries can not only address the challenges of ageing but also harness its potential benefits.

1. Introduction

The ‘demographic timebomb’ has traditionally been used to refer to the potential problems that countries face stemming from declining birth rates and an ageing population (Ehrlich and Ehrlich, 1968). This transition, marked by a higher proportion of older individuals and a shrinking working-age population, presents a wealth of possible economic and social challenges, including higher healthcare, social care and pension costs, and reduced economic growth. However, more recent academic discourse, including Hill (2007), critique this narrative, suggesting that it overlooks social adaptability, potential policy reforms, and the broader economic contributions of the ageing population. Debates continue over the appropriateness and timing of policy responses to ‘defuse the timebomb’ and the anticipated implications for future generations. This essay contributes to the debate by examining demographic ageing as both a current and future challenge, arguing that although the effects differ across contexts, the convergence of low fertility, rising longevity and potential labour shortages necessitates proactive, long-term strategies rather than short-term fixes.

2. The causes of population ageing

2.1. The European context

Europe is now “the world’s oldest continent” (Romei, 2020). Southern Europe has a fertility rate of 1.37, far below the replacement rate of 2.1, and Portugal, Greece, Italy and Spain are among the top ten world economies with the lowest number of births per woman (Romei, 2020). Poor job prospects, low wage expectations, and an inflexible labour market, coupled with a lack of family-friendly policies and the persistence of traditional gender roles within the family, with women shouldering many of the household responsibilities, have been proposed as possible causes (Romei, 2020). In contrast, in Eastern Europe, high rates of emigration, mainly of young economically active adults has resulted in a multiplied decrease in the working-age proportion of the population because natural increase has reduced significantly as young workers have left. From a capitalist viewpoint, fewer young workers entering the workforce potentially creates labour shortages, reduced tax revenues, and a reduction in economic growth due to the absence of innovation and consequently productivity that younger workers bring (The Economist, 2023). Compounding the low birth rate, life expectancy in Europe has increased by approximately 30 years over the last century (Our World in Data, 2022). This unprecedented demographic shift is likely to exert significant pressure on social and health-care services, as well as pension schemes, potentially straining public finances and constraining government spending in other areas. The European Commission forecasts that spending on pensions and healthcare for the elderly, which currently accounts for 25% of GDP in the EU, will increase by 2.3% by 2040 (Romei, 2020).

However, these older citizens are significantly healthier than in previous generations, thereby mitigating the potential fiscal burden associated with population ageing. Spijker and MacInnes (2013) argue that this healthier cohort are continuing to participate in voluntary unpaid work for longer and may also have accumulated significant assets. The Local Government Association’s report, ‘Ageing: The Silver Lining’ (2015), supports this view, reframing ageing as an economic and social benefit, with older adults contributing through employment, caregiving, mentoring, and cultural engagement. An estimated 60% of UK adults above state pension age pay income tax on their earnings and often possess substantial spending power, with surveys suggesting that they often make significant financial contributions to younger relatives (August, 2024; Downey, 2017). Their contribution to the ‘silver economy’ through consumption in sectors such as healthcare, travel, and leisure, and their participation in voluntary sectors enhances community cohesion and supports overstretched public services (Runde, Sandin and Kohan, 2021). Global healthy life expectancy is increasing (WHO, 2019) and most health-care costs are known to be incurred in the final months of life (Spijker and MacInnes, 2013) suggesting that longer, healthier lives may not significantly increase health-care expenditure. Technological advances, including telemedicine and online information platforms, further support healthy and active ageing by providing accessible, educational health-care services (Runde, Sandin and Kohan, 2021). Spijker and MacInnes (2013) calculated a ‘real elderly dependency ratio’ as the sum of people with a remaining life expectancy of less than 15 years, divided by the number of employed people. This indicates that dependency has fallen by one third over the past four decades, with the real elderly dependency ratio in Europe set to stabilise near its current level in the future. Nonetheless, concerns remain regarding the long-term affordability of pensions. Brown (2014) suggests that although health-care costs may not rise as the population ages, the number of people living for longer above the pension age will increase and therefore spending on pension costs will inexorably rise unless the statutory pension age increases.

2.2. The Japanese context

In common with Europe, Japan has an ageing population with the world’s highest longevity at around 85 years (Takasaki et al., 2012). However, Japan has had a fertility rate below the accepted replacement rate since the 1960s and so the labour force is shrinking (Takasaki et al., 2012). Japan has reached a critical threshold, with projections indicating that in eight years, the number of women of reproductive age will fall to a point where population decline cannot be reversed (Siripala, 2023). The low birth rates have been attributed to difficulties with women returning to work after having children, inequality in child rearing responsibilities, as well as a lack of family friendly policies in the workplace. Employees are under pressure to work long hours, and the economy has been criticised as being “labour focused rather than people focused” (Siripala, 2023). In 2023, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio proposed a ‘smart spending’ initiative to stimulate economic growth and combat population decline. This focused on tax reductions, subsidies and investment in strategic sectors to stimulate economic growth, alongside more financial assistance for parents, improvements in preschool education and maternity services, and workplace reforms to encourage higher birth rates. However, Japan’s public debt is twice its GDP and so any expenditure concerns policymakers as any future need for revenue possibly requires tax increases which are likely to disproportionally affect younger generations.

2.3. Experiences of Developing Countries

An ageing population is increasingly affecting developing countries, challenging the assumption that it is exclusive to developed nations. By 2050, approximately 80% of those over sixty will live in low- and middle-income countries (The Lancet Healthy Longevity, 2021). These countries face unique demands including inadequate health-care infrastructure, financial constraints, and insufficient training and research in elderly care (The Lancet Healthy Longevity, 2021; Shetty, 2012). It is crucial that developing countries acknowledge and implement proactive strategies to address the consequences of this changing demographic.

3. Responses to Population Ageing

Effectively managing population ageing requires a multifaceted approach that supports social inclusion, health, education and economic participation throughout life.

3.1. Migration

Although the world’s population is currently rising, this increase is not generally occurring in those countries with an ageing population. Therefore, it has been suggested that allowing migration of young people to countries with an ageing population may be a possible solution to compensate for dwindling birth rates in these areas (d’Artis and Patrizio, 2017).

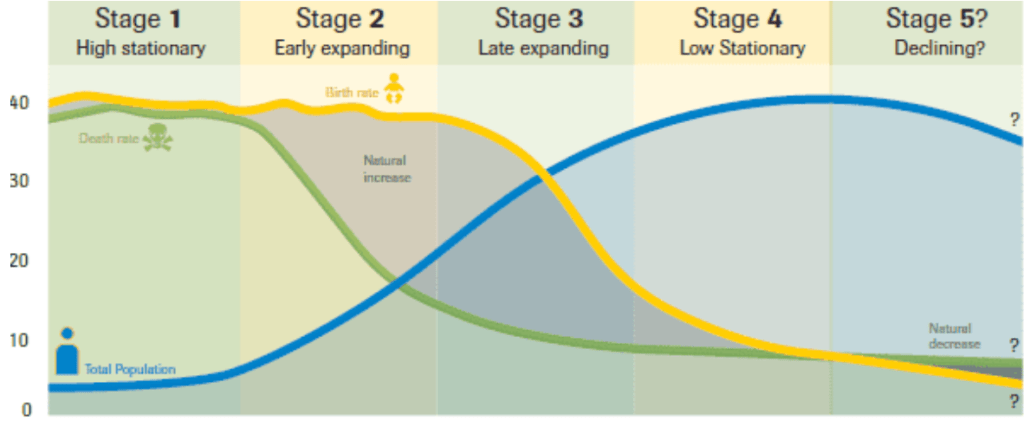

The total world population has risen exponentially, reaching an estimated eight billion by 2022 (UN, 2022), but it is predicted to peak in approximately 2060 at around ten billion before beginning to decline (Shute, 2022). In the last 25 years, almost all the population growth has happened in developing economies, mainly in Asia, Oceania, and Africa. Since 1950, the share of people living in these regions has increased from 66% to 83% (UNCTAD, 2022). By the middle of this century, UN data has shown that the only countries who are likely to be in Stage 3 of the Demographic Transition Model (Figure 1) and enjoying the demographic dividend of youth (the growth in an economy resulting from the increase in the proportion of economically active people) are in sub-Saharan Africa. However, any migration of people from one area to another brings with it challenges, both in the sending and receiving countries.

Figure 1: The Demographic Transition Model (Grover, 2021)

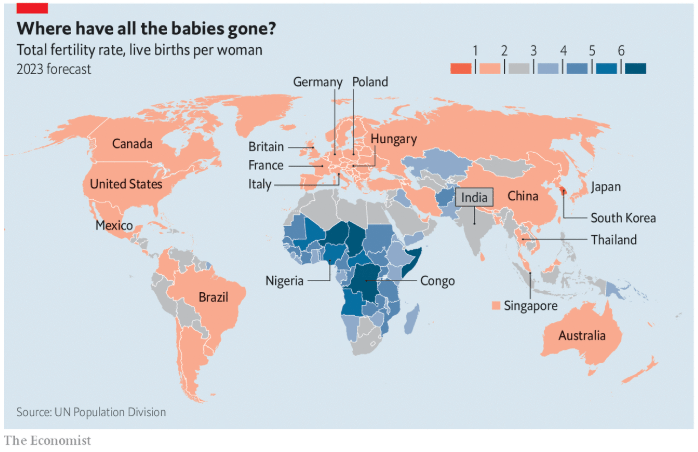

The emigration of skilled workers from low-income countries to more developed areas, known as brain drain, potentially causes labour and skills shortages in the donor country, hindering economic diversification and growth. Mitigation of migration by governments in developing countries is needed to retain highly trained young workers for future development. Recruitment of these workers by governments of more developed areas to counter their ageing population is considered ethically dubious and is seen by some as the taking of valuable human resources, perhaps analogous to neo-colonialism (Skeldon, 2005). Recently the Nigerian government proposed a bill requiring medical graduates to work in Nigeria for five years before emigrating to curb brain drain (Devi, 2023). Nigeria itself is short of medics and in 2018 only 12% of Nigeria’s population had a tertiary education qualification (World Bank, 2022). However, the bill provoked widespread opposition by Nigerian medics, who are often poorly paid with limited career pathways and insufficient training. Furthermore, as more countries experience an ageing population, educated migrants will become harder to find. Sub-Saharan Africa is the only region of the world likely to be a potential donor of migrants in the next half century due to the current high fertility rate (Figure 2). However, improved access to contraception and education particularly for girls, has meant that the birth rate is falling in these countries too. Matthias Doepke, noted that falling birth rates are no longer limited to wealthier countries, saying “There’s a global convergence in women’s aspiration for careers and family life” (The Economist, 2023).

Figure 2: Choropleth map of forecasted fertility rate by country for 2023 (The Economist, 2023)

The immigration of workers into countries with an ageing population also brings challenges in the host country. Japan, along with many other countries, has always shown resistance to immigration. In the UK, Brexit was arguably due to a misalignment of partial truths regarding immigration, whereby despite the low demands of healthy, young immigrants on health and social care services, the pressures on the NHS and schools were mistakenly perceived by some as being caused by migration. Despite estimates by the European Commission that immigration increases the annual GDP of a host country by 0.2% to 1.4% above the baseline growth (d’Artis and Patrizio, 2017), the politicisation of the issue of immigration has led to polarised viewpoints and deep socio-political divisions. In the 2024 USA elections, Trump made migration a key policy with his promise of “mass deportations” and Reform UK’s anti-immigration rhetoric significantly influenced UK electoral outcomes in 2024 (Heath et al., 2024). Political policies on migration often yield short-term electoral gains for parties; however, governments must prioritise long-term demographic planning, considering that the demographics of the population change slowly. These opposing agendas can be difficult to align.

3.2. Alternative Approaches

In the long term, immigration is unlikely to fully compensate for the declining birth rates observed in many developed countries. Some European countries have offered financial incentives such as child benefit payments, tax incentives, or one-off payments to attempt to increase birth rates (BBC News, 2020). These measures, coupled with increased job flexibility and paid parental leave aim to increase the appeal of having children. However, their effectiveness has been limited (BBC News, 2020).

Other countries have focused on increasing workforce productivity to mitigate the effects of an ageing population, particularly through government investment in education, training, and healthcare. They consider that with investment, the population of the country can develop skills essential to a thriving workforce, thus ensuring adequate care for the elderly. As the potential workforce shrinks, maximising the output of everyone in it becomes essential, particularly in middle-income countries such as China, where there are millions who receive an inadequate education and so contribute little to the capitalist economy.

Technology is also being used to maximise economic productivity. Japan has adopted a range of innovative digital solutions to support its ageing population and alleviate pressure on human caregivers. Robotic caregivers, smart home technologies, telemedicine, targeted investments in elderly care training, and digital literacy aim to enable health-care professionals to deliver more effective, technology-enabled health-care services and promote independence in the elderly (Runde, Sandin and Kohan, 2021). However, further research into the long-term effectiveness of these programmes is needed.

Perhaps a potentially more sustainable approach to managing the changing demographic landscape is the restructuring of retirement and pension systems to encourage older individuals to remain in employment for longer. Recent research suggests that today’s 70-year-olds have the same cognitive and physical capabilities as the average 53-year-old in 2000 and so the International Monetary Fund is advocating an increase in the pension age (O’Donnell, 2025). While such suggestions emphasise the economic utility of older adults, others point out that this focus on extended working life risks reinforcing structural inequalities, especially when workplace conditions, health disparities and job quality vary widely across populations (Hagemann and Scherger, 2016). Katz and Calasanti (2014) cautioned that framing older adults primarily in terms of economic utility can reduce ageing to a matter of productivity, marginalising concerns of wellbeing and social equity. Germany’s gradual increase in the statutory pension age from 65 to 67, initiated in 2012, has contributed to higher labour force participation among older adults, with the employment rate for those aged 55-64 rising from approximately 62% in 2012 to 72% by 2021 (DeStatis, 2023). However, higher participation rates do not necessarily equate with improved quality of life (Gebremariam and Sadana, 2019). In the UK, the state pension age will increase to 67 by 2028 (Pensions Act, 2014). However, these policies are often extremely unpopular with workers, as evidenced by the protests in France in 2023, meaning many governments, especially those who are focused on short-term decisions, are reluctant to consider them (Graham-Harrison, 2023). This highlights that demographic policy is not simply a technical or economic question but also a political and ethical one about intergenerational fairness and the dignity of later life. Collective responsibility, universal welfare provision and the redistribution of resources may be required to ensure this.

4. Conclusion

Globally there has been a demographic shift to an ageing population. However, this population is healthier than in previous generations and ageing can be seen as an economic and social asset, with older adults contributing through employment, caregiving, mentoring, and cultural and political engagement. Yet the value of older people should not solely be seen from a capitalist perspective. From an ethical viewpoint it is important to value people’s dignity, autonomy and social worth in later life, regardless of age, health or economic status.

Projections of increased public spending on pensions, health care and social care, and a reduced labour force with a decreased economic output remain a concern. However, most health-care costs are incurred in the final months of life and by increasing the pension age, investing in human capital, designing cohesive migration strategies, embracing technological advances, and supporting families, many of these impacts can be mitigated. Although these proactive policy interventions may be politically unpopular, adopting a multifaceted approach will ensure that any demographic timebomb explodes with a pop rather than with a bang.

References

August G. (2024, June 4.) “Fact check: Pensioners paid £19.5 billion in income tax in year ending 2022,” The Standard, Available at: https://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/rishi-sunak-pensioners-labour-conservative-b1162137.html (accessed 29/09/25)

BBC News (2020, January 15.) “How do countries fight falling birth rates?” BBC News,

Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-51118616 (accessed 03/04/23)

Brown G. (2015, December 18.) “Living too long: The current focus of medical research on increasing the quantity, rather than the quality, of life is damaging our health and harming the economy,” EMBO reports, Vol. 16, Issue 2, pp.137–141. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201439518. (accessed 22/04/25)

Dakar and Kano (2023, April 5.) “The world’s peak population may be smaller than expected,” The Economist, Available at: https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2023/04/05/the-worlds-peak-population-may-be-smaller-than-expected (accessed 03/04/23)

d’Artis K. and Patrizio L. (2017, April) “Long-term Social, Economic and Fiscal Effects of Immigration into the EU: The Role of the Integration Policy,” JRC Technical Reports, doi:10.2760/999095 (accessed 03/04/23)

DeStatis (2023, January 19.) “Employment of older people in Germany and the EU markedly up in the last 10 years,” Statistisches Bundesamt, Available at: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2023/01/PE23_N003_13. (accessed 26/04/25)

Devi S. (2023, June 3.) “Brain drain laws spark debate over health worker retention,” The Lancet,

Vol. 401, No. 10391, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01113-3 (accessed 04/06/23)

Downey C. (2017, May 24.) “A third of planned retirees still financially supporting family,” SkyNews, Available at: https://news.sky.com/story/a-third-of-planned-retirees-still-financially-supporting-family-10890569? (accessed 29/09/25)

Ehrilch P. and Ehrilich A. (1968) “The Population Bomb,” Sierra Club/Ballantine Books (accessed 03/04/23)

Gebremariam KM. and Sadana R. (2019, September 5.) “On the ethics of healthy ageing: setting impermissible trade-offs relating to the health and well-being of older adults on the path to universal health coverage,” International Journal for Equity in Health, Vol. 18, No. 140, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-0997-z (accessed 28/09/2025)

Graham-Harrison, E., McCurry, J. (2023, January 22.) “Ageing Planet: the new demographic

timebomb,” The Observer, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/22/ageing-planet-the-new-demographic-timebomb (accessed 03/04/23)

Grover D. (2014, October 13.) “What is the Demographic Transition Model?” Population Education, Available at: https://populationeducation.org/what -demographic-transition-model/ (accessed 04/06/23)

Hagemann S. and Scherger S. (2016, December) “Increasing pension age — Inevitable or unfeasible? Analysing the ideas underlying experts’ arguments in the UK and Germany,” Journal of Aging Studies, Vol. 39, pp. 54-65, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2016.09.004 (accessed 29/09/25)

Heath O., Prosser C., Southall H. and Aucott P. (2024, November 30.) “The 2024 General Election and the Rise of Reform UK,” The Political Quarterly, Vol. 96, Issue 1, pp. 91-101, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.13484 (accessed 17/04/25)

Katz S. and Calasanti T. (2014, April 18.) “Critical Perspectives on Successful Aging: Does It “Appeal More Than It Illuminates”?” Gerontologist, Vol. 55, No. 1, pp. 26-33, Available at: doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu027 (accessed 28/09/25)

Local Government Association (2015, June), “Ageing: the silver lining. The opportunities and challenges of an ageing society for local government,” Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/ageing-silver-lining-oppo-1cd.pdf (accessed 08/04/25)

O’Donnell P. (2025, April 17.) “Baby boomers told to get back to work as IMF calls for pension age rise to boost economy: ’70 is new 50!’,” GBNews, Available at: https://www.gbnews.com/money/retirement-baby-boomer-imf-pension-age-economy (accessed 18/04/25)

Pensions Act 2015. (c.18.1). London: The Stationary Office (accessed 11/06/23)

Our World in Data (2022) “Life Expectancy 1770-2021,” Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/life-expectancy (accessed 11/06/23) Data Published by: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022). World Population Prospects 2022, Online Edition; Zijdeman et al. (2015) (via clio-infra.eu); Riley, J. C. (2005). Estimates of Regional and Global Life Expectancy, 1800-2001. Population and Development Review, 31(3), 537–543. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3401478

Romei V. (2020, January 14.) “In charts: Europe’s demographic time-bomb,” Financial Times,

Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/49e1e106-0231-11ea-b7bc-f3fa4e77dd47 (accessed 03/04/23)

Runde D., Sandin L. and Kohan, A. (2021, September 27.) “Addressing an Aging Population through Digital Transformation in the Western Hemisphere,” http://www.csis.org, Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/addressing-aging-population-through-digital-transformation-western-hemisphere (accessed 08/04/25)

Shetty P. (2012, April 7.) “Grey matter: ageing in developing countries,” The Lancet, Vol. 379, Issue 9823, pp.1285–1287, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60541-8. (accessed 08/04/25)

Shute J. (2022, November 25.) “A demographic timebomb is about to reshape our world,”The

Telegraph, Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2022/11/25/world-population-increase-peak-chart-age-gender/ (accessed 03/04/23)

Siripala T. (2023, January 28.) “Japan’s Population Crisis Nears Point of No Return,” The Diplomat, Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2023/01/japans-population-crisis-nears-point-of-no-return/ (accessed 03/04/23)

Skeldon R. (2005, November) “Globalization, Skilled Migration and Poverty Alleviation: Brain Drains in Context,” Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty, Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08c7b40f0b64974001248/WP-T15.pdf (accessed 28/09/2025)

Spijker and MacInnes (2013, November 16.) “POPULATION AGEING The timebomb that isn’t?” Vol. 347:f6598, pp. 20-22, doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6598 (accessed 03/04/23)

Takasaki et al. (2012, October 16.) “Japan’s answer to the economic demands of an ageing population,” Vol. 345:e6632 (accessed 04/06/23)

Textor C. (2023, February 28.) “Population growth in China from 2000 to 2022,” Statista, Available at:

https:// www.statista.com/statistics/270129/population-growth-in-china/#:~:text=The%20Chinese%20population%20reached%20a,to%20take%20over%20in%202023. (accessed 03/04/23)

The Economist (2023, May 30.) “It’s not just a fiscal fiasco: greying economies also innovate less,”

Available at: https://www.economist.com/briefing/2023/05/30/its-not-just-a-fiscal-fiasco-greying-economies-also-innovate-less (accessed 04/06/23)

The Lancet Healthy Longevity (2021, April) “Care for ageing populations globally,” Vol. 2 Issue 4, e180, https://doi.org/10.1016/s2666-7568(21)00064-7 (accessed 17/04/25)

United Nations (2022) “Global issues: Population,” Available at: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/population.

UNCTAD (2022, November 15.) “Now 8 billion and counting: Where the world’s population has

grown most and why that matters,” Available at: https://unctad.org/data-visualization/now-8-billion-and-counting-where-worlds-population-has-grown-most-and-why (accessed 29/04/23)

World Bank (2022) “School enrolment, tertiary (% gross) – Nigeria,” Available at:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.TER.ENRR?end=2018&locations=NG&start=1975&view=chart (accessed 04/06/23)

World Health Organisation (2019) “GHE: Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy,”Available at: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy (accessed 29/04/23)

#Write for Routes

Are you 6th form or undergraduate geographer?

Do you have work that you are proud of and want to share?

Submit your work to our expert team of peer reviewers who will help you take it to the next level.

Related articles