Volume 4 Issue 3

By Kalani Foster, University of York

Citation

Foster, K. 2025. Investigating the Relationship Between Environmental Values and Public Perceptions of Geoengineering Technologies. Routes, 4(3): 198-217.

Abstract

Environmental values act as a focal point for the evaluation of new policies, actions, and groups, particularly concerning emergent attitude objects, as values provide a stable and enduring basis for attitude formation. However, literature has not yet analysed the impact of environmental values on attitude formation around geoengineering perceptions. This study utilised an online questionnaire of UK publics to connect environmental values as measured through the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) and its subthemes to perceptions of geoengineering, carbon dioxide removal, and solar radiation modification. Results indicate that, as a whole, environmental values do not consistently underpin support for geoengineering research and deployment except the eco-crisis subtheme. Instead, geoengineering represented an impending climate crisis among those with a higher NEP score in which less trust was placed in policymakers, and concern for this crisis eventually overruled concern for geoengineering’s under-researched implications. Future work should study how beliefs regarding climate urgency impact public perceptions of geoengineering.

1. Introduction

Climate change mitigation is a key imperative driving geoengineering. Defined as “deliberate large-scale interventions to alter the Earth’s climate to counteract climate change” (Tsipiras and Grant, 2022, p.27), geoengineering technologies broadly fall under two categories: Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR), which removes and stores carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and Solar Radiation Management (SRM), which modifies the albedo of the Earth to reflect sunlight back into space, cooling the Earth (Raimi, 2021). CDR has comparatively low risks, but mitigates climate change slowly, whereas SRM works quickly but overlooks carbon dioxide concentrations and has more unknown externalities (ibid.).

Publics generally know little about geoengineering (Raimi, 2021; Carvalho and Riquito, 2022) or are worried about its environmental externalities (Oomen and Meiske, 2021). Consequently, participants support research but not development (Pamplany et al., 2020) or frame geoengineering as an umbrella term under which they discuss sociopolitical or socioeconomic considerations impacted by geoengineering (Carvalho and Riquito, 2022). Publics are also often excluded from geoengineering debates and therefore unaware of its implications (Raimi, 2021), establishing a need to continuously investigate public awareness and attitudes.

Individuals’ actions are rooted in their values, or trans-situational goals that vary in importance (Bouman et al., 2021). Values are relatively stable over time and are guidelines in which policies, actions, and groups are evaluated upon, underpin perceptions, and facilitate attitude formation (Kim and Stepchenkova, 2020). Analysing environmental values is especially useful in exploring emergent attitude objects, as values provide a stable, enduring basis for attitude formation (de Groot and Thøgersen, 2018). To date, research has not yet explicitly examined the relationship between environmental values and geoengineering perceptions, despite geoengineering’s emergence as a new attitude object.

The New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale recognises that nature’s intrinsic value is being compromised by human activity (Dunlap et al., 2000). It consists of fifteen statements which respondents rate their level of agreement to, and the corresponding numeric values are used for analysis; those with higher environmental values are hypothesised to achieve a higher score (ibid.). The NEP covers five themes, with three questions each (see Tables 1 and 2 below). Empirical research has shown that there is a positive and significant association between a higher NEP score and pro-environmental travelling behaviour, purchasing behaviour, and day-to-day activities (Derdowski et al., 2020): for example, Taiwan undergraduates were more likely to report higher recycling intentions the higher their NEP score (Yu et al., 2019) and a higher NEP score was correlated with willingness to pay for renewable energy in Greece (Ntanos et al., 2019). Environmental concern through the NEP was also positively correlated with recycling and community action and negatively correlated with littering (Agissova and Sautkina, 2020), showing that the NEP can be correlated with pro-environmental action.

| Theme | Definition |

| Balance of nature | The belief that the balance of nature can be easily upset by human activities. |

| Eco-crisis | The belief that humans are causing detrimental harm to the physical environment and that an environmental or ecological catastrophe is likely to occur. |

| Anti-exemptionalism | The belief that human beings are not exempt from the constraints of nature. |

| Limits to growth | The belief that Earth has limited resources and that society can only grow to a certain point. |

| Anti-anthropocentrism (human domination) | The belief that nature has inherent value besides human uses that require modification and/or control of the environment. |

Table 1: Themes present within the NEP (Amburgey and Thoman, 2012; Goble, 2018)

| Statement | Theme | |

| 1 | We are approaching the limit of the number of people the Earth can support. | Limits to growth |

| 2 | Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs. | Anti-anthropocentrism (human domination) |

| 3 | When humans interfere with nature, it often produces disastrous consequences. | Balance of nature |

| 4 | Human innovation will ensure that we do not make the Earth unlivable. | Anti-exemptionalism |

| 5 | Humans are seriously abusing the environment. | Eco-crisis |

| 6 | The Earth has plenty of natural resources if we just learn how to develop them. | Limits to growth |

| 7 | Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist. | Anti-anthropocentrism (human domination) |

| 8 | The balance of nature is strong enough to cope with the impacts of modern industrial nations. | Balance of nature |

| 9 | Despite our special abilities, humans are still subject to the laws of nature. | Anti-exemptionalism |

| 10 | The so-called “ecological crisis” facing humankind has been greatly exaggerated. | Eco-crisis |

| 11 | The Earth is like a spaceship with very limited room and resources. | Limits to growth |

| 12 | Humans were meant to rule over the rest of nature. | Anti-anthropocentrism (human domination) |

| 13 | The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset. | Balance of nature |

| 14 | Humans will eventually learn enough about how nature works to be able to control it. | Anti-exemptionalism |

| 15 | If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe. | Eco-crisis |

Table 2: The NEP and corresponding themes of each statement – even numbered statements must be reverse-scored prior to statistical analysis (modified from Hawcroft and Milfont, 2010)

There has been a lack of research connecting environmental values to geoengineering perceptions. This research project therefore aims to examine the relationship between environmental values of respondents and perceptions of geoengineering through two objectives:

- To investigate public perceptions of geoengineering, CDR, and SRM

- To measure environmental values using the New Ecological Paradigm scale, and explore the relationship between environmental values and geoengineering perceptions.

This study adopted a mixed-methods, albeit mostly quantitative, approach with primary data collected through an online Qualtrics questionnaire utilising Liker-style and open-ended questions (Appendix A). UK-based respondents were invited to participate through social media using a self-selection approach, meaning that respondents volunteered to participate rather than be recruited (Sharma, 2017). Self-selection sampling may result in self-selection bias as respondents might participate only if they feel they are familiar with geoengineering and can lead to an unrepresentative sample (ibid.), so demographic audiences were monitored while the questionnaire was active to ensure it reached a diverse sample.

The questionnaire garnered 104 responses. Spearman’s-Rank Order Correlations were performed to understand the relationship between NEP themes and geoengineering perceptions because it determines the strength and direction of linear relationships (Liefländer et al., 2018). Through this, it can be seen whether or not certain variables — such as environmental values measured through the NEP — tend to increase or decrease as other variables increase — such as attitudes towards geoengineering, CDR, and SRM. Additionally, demographic data in this study was more diverse than UK demographics, but because data is not inherently indicative of overall UK perceptions of geoengineering future studies should analyse these relationships utilising a larger and more representative sample.

| Demographics for Analysis | ||||

| Demographic category | Demographic information | Questionnaire total (n) | Percentage of overall survey sample | Percentage of 2021 UK population |

| Gender identity | Man | 42 | 40.38% | 49% |

| Woman | 59 | 56.73% | 51% | |

| Non-binary | 2 | 1.92% | 0.06% | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.96% | Not given | |

| Total gender identity | 104 | – | – | |

| Age | 18-29 | 59 | 56.73% | 12.60% |

| 30-49 | 23 | 22.12% | 26.30% | |

| 50+ | 21 | 20.19% | 38.04% | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.96% | Not given | |

| Total age | 104 | – | – | |

| Ethnicity | Any white background | 60 | 57.69% | 81.7% |

| Any mixed or multiple ethnic background | 37 | 35.58% | 18.3% | |

| Not known | 2 | 1.92% | Not given | |

| Prefer not to say | 5 | 4.81% | Not given | |

| Total ethnicity | 104 | – | – | |

| Level of education | GCSE, O-level, CSE | 3 | 2.88% | 9.6% |

| Vocational qualification | 4 | 3.85% | 5.3% | |

| A-level or equivalent | 23 | 22.12% | 16.8% | |

| Still studying | 19 | 18.27% | 3.95% | |

| Bachelor degree or equivalent | 32 | 30.77% | 33.8% | |

| Masters, PhD, or equivalent | 20 | 19.23% | ||

| Other | 3 | 2.88% | 2.8% | |

| Total level of education | 104 | – | – | |

| Employment status | Working full time | 38 | 36.54% | 56.54% |

| Working part time | 13 | 12.5% | 19.09% | |

| Self employed | 5 | 4.81% | 9.91% | |

| Unemployed | 3 | 2.88% | 3.7% | |

| Retired | 8 | 7.69% | Not given | |

| Student | 37 | 35.58% | 2.31% | |

| Total employment status | 104 | – | – | |

| Political party | Lib dem | 15 | 14.42% | 9% |

| Conservative | 20 | 19.23% | 33% | |

| Labour | 29 | 27.88% | 37% | |

| Green | 13 | 12.5% | 7% | |

| Did not vote | 18 | 17.31% | Not given | |

| Other/Prefer not to say | 9 | 8.65% | 6% | |

| Total political party | 104 | – | – | |

Table 3: Demographic information of questionnaire respondents as used for statistical analysis compared to overall percentages of the UK population rounded to the nearest tenth (UK census, 2021)

3.1 General Perceptions

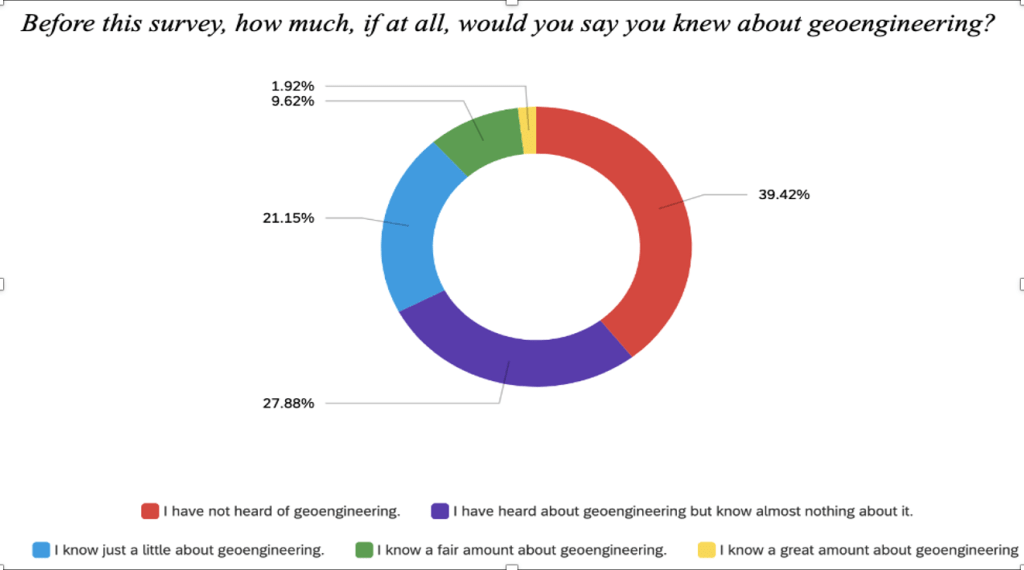

Most respondents were unfamiliar with geoengineering, as only 11.54% (n=12) knew a fair or great amount about geoengineering (Figure 1). Results should thus be treated as baseline measures of initial perceptions.

| Figure 1: Self-assessed knowledge of geoengineering prior to reading the supplemental information in the questionnaire |

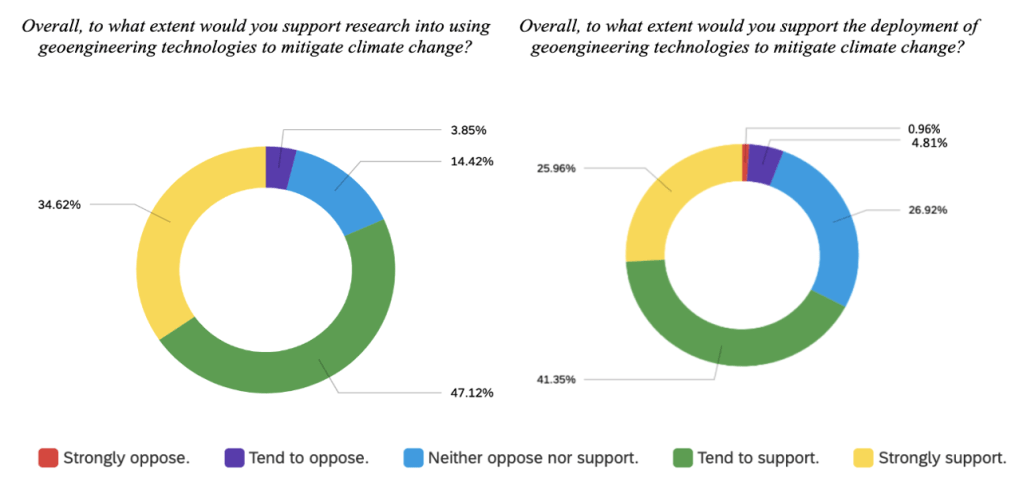

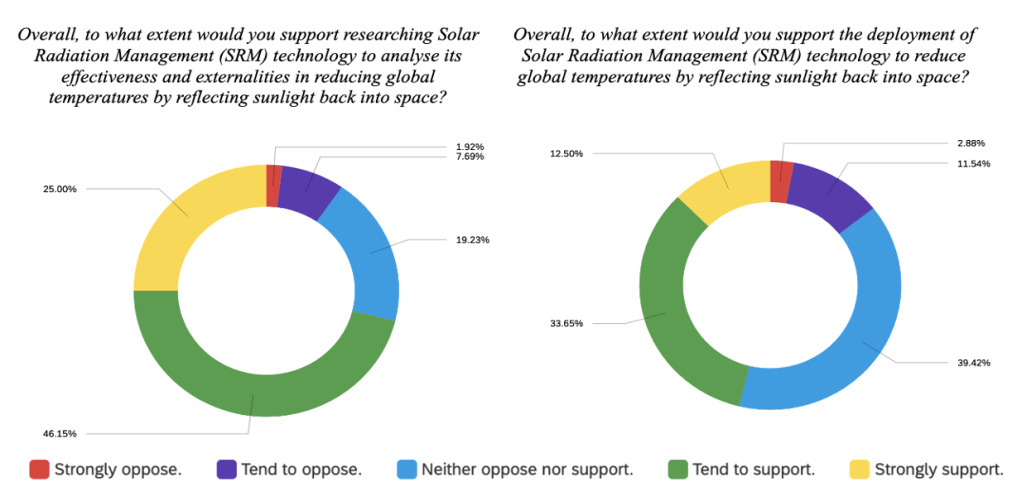

As seen in Figure 2, more support was seen for geoengineering research than deployment: no respondents opposed research, and only 5.77% (n=5) opposed deployment. Similarly, most respondents were supportive of CDR research and deployment (Figure 3) and SRM research (71.15%, n=74) (Figure 4). However, 39.42% (n=41) of respondents neither opposed nor supported SRM deployment, reflecting the general lack of knowledge in SRM deployment.

| Figure 2: Levels of support for geoengineering research and deployment |

| Figure 3: Levels of support for CDR research and deployment |

| Figure 4: Levels of support for SRM research and deployment |

As seen in Figure 5, geoengineering made most respondents (51.45%, n=53) think that climate change risks were worse than they thought. 26.21% (n=27) of respondents disagreed, but may have already believed that climate change is significant. Discussion will analyse this alongside environmental values.

| Figure 5: Respondents who believe that geoengineering shows that the risks of climate change are worse than they had thought |

Figure 6 displays the percentage of respondents who believe that scientists and policymakers have a better handle on tackling climate change knowing geoengineering is being researched. This presents similar levels of agreement (42.72%, n=44) and disagreement (44.66%, n=46). However, respondents’ trust or distrust in scientists and policymakers may be unaffected by geoengineering, so discussion will analyse this in relation to environmental values.

| Figure 6: Respondents who believe that geoengineering being researched means that scientists and policymakers have a better handle on tackling climate change than they had previously thought |

Respondents often opposed geoengineering due to its unknown externalities (Table 4), and supported geoengineering to combat climate emergencies (Table 5). Climate emergencies further dominated support, as some respondents noted that we “are almost out of time to act” or that “there is no going back now.” Climate urgency could therefore be imperative in predicting geoengineering support.

| Are there any other reasons as to why you might oppose geoengineering? |

| I simply do not think we will ever know enough to pursue and justify our arrogant behaviour towards nature and the environment. We also can’t predict the consequences of these geoengineering approaches. Imposing geoengineering adds more threat to the butterfly effect on the planet and potentially beyond. |

| Don’t really know too much about it, seems like it’s mostly speculation. |

| I need to know more about potential side effects. Interfering with nature on the level of placing particles in the atmosphere sounds risky to me. |

| I don’t oppose it, but I do have questions. Where do the particles go? Will it damage our solar system? Is it a temporary solution to overpopulation? |

| It might be too much power for humans. I may be wrong but there might not be a lot of research on this topic. |

| I saw the movie “Snowpiercer” where scientists miscalculated their use of stratospheric aerosol injection and accidentally caused another ice age. Not sure if that’s accurate, but causing climate catastrophe in the other direction makes me nervous. |

| The risk levels vary hugely for different types of geoengineering methods. For example, aerosols reflecting sunlight away from Earth must be calculated perfectly to avoid reflecting too much and causing a decrease in global temperatures. This is a relatively new suggestion so I would be very hesitant to support it without significant improvements in research and volume of supporting data. |

Table 4: Other reasons why some respondents might oppose geoengineering

| Are there any other reasons as to why you might support geoengineering? |

| We have destroyed the world and it’s our responsibility to fix it. Therefore we may be interfering with nature but we have already done this. |

| Could create a lot of jobs and help us continue to take what we need from nature to continue innovating and developing. |

| We are almost out of time to act, at the end of the day Earth will be here with or without us, we need to do this for our sake and our survival. |

| Because if it is being researched, it is because there is no going back now. Humans have already interfered with the environment enough and implementing it will not be another form of intervention but with a benevolent aim (e.g., Internet cables going across our oceans, massive deforestation/fishing). |

| It’s difficult to support geoengineering without knowing the results of research, but I support it as a last resort if other methods of mitigation fail to take off in time. |

| Job creation, need to just go for development at this point in time so time is not wasted on research before it is too late. |

Table 5: Other reasons why some respondents might support geoengineering

3.2 Environmental Values

Table 6 analyses the overall NEP. The statement with the highest average NEP score (4.50) acknowledged the potential of an ecological catastrophe (#15). Statement 4 had the second lowest NEP score (2.86) regarding human innovation ensuring that Earth remains livable, implying that respondents have faith in technological innovation, potentially justifying geoengineering support.

| Statement | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | Mean; std dev NEP score | |

| 1 | We are approaching the limit of the number of people the Earth can support. | 9 (8.65%) | 18 (17.31%) | 12 (11.54%) | 45 (43.27%) | 20 (19.23%) | 3.47; 1.22 |

| 2 | Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs. | 10 (9.62%) | 43 (41.35%) | 18 (17.31%) | 28 (26.92%) | 5 (4.81%) | 3.24; 1.10 |

| 3 | When humans interfere with nature, it often produces disastrous consequences. | 2 (1.92%) | 3 (2.88%) | 20 (19.23%) | 44 (42.31%) | 35 (33.65%) | 4.03; 0.90 |

| 4 | Human innovation will ensure that we do not make the Earth unlivable. | 8 (7.69%) | 24 (23.08%) | 25 (24.04%) | 39 (37.50%) | 8 (7.69%) | 2.86; 1.10 |

| 5 | Humans are seriously abusing the environment. | 1 (0.96%) | 3 (2.88%) | 6 (5.77%) | 39 (36.54%) | 8 (7.69%) | 4.39; 0.80 |

| 6 | The Earth has plenty of natural resources if we just learn how to develop them. | 1 (0.96%) | 15 (14.42%) | 18 (17.31%) | 41 (39.43%) | 29 (27.88%) | 2.21; 1.03 |

| 7 | Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist. | 1 (0.96%) | 5 (4.81%) | 11 (10.58%) | 29 (27.88%) | 58 (55.77%) | 4.33; 0.91 |

| 8 | The balance of nature is strong enough to cope with the impacts of modern industrial nations. | 32 (30.77%) | 44 (42.31%) | 11 (10.58%) | 12 (11.54%) | 5 (4.81%) | 3.83; 1.13 |

| 9 | Despite our special abilities, humans are still subject to the laws of nature. | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | 8 (7.69%) | 46 (44.23%) | 50 (48.08%) | 4.40; 0.63 |

| 10 | The so-called “ecological crisis” facing humankind has been greatly exaggerated. | 47 (45.19%) | 36 (34.62%) | 16 (15.38%) | 3 (2.88%) | 2 (1.94%) | 4.18; 0.93 |

| 11 | The Earth is like a spaceship with very limited room and resources. | 4 (3.85%) | 22 (21.15%) | 29 (27.88%) | 40 (38.46%) | 9 (8.65%) | 3.27; 1.01 |

| 12 | Humans were meant to rule over the rest of nature. | 43 (41.75%) | 41 (39.81%) | 10 (9.71%) | 7 (6.80%) | 2 (1.94%) | 4.13; 0.97 |

| 13 | The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset. | 1 (0.96%) | 15 (14.42%) | 18 (17.31%) | 44 (42.31%) | 26 (25.00%) | 3.76; 1.01 |

| 14 | Humans will eventually learn enough about how nature works to be able to control it. | 14 (13.46%) | 46 (44.23%) | 18 (17.31%) | 22 (21.15%) | 4 (3.85%) | 3.41; 1.08 |

| 15 | If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe. | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (1.92%) | 6 (5.77%) | 34 (32.69%) | 62 (59.62%) | 4.50; 0.69 |

| Total mean NEP score (15-75): 56.01 | |||||||

Table 6: Respondents’ level of agreement with the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP)

Tables 8-12 (Appendix B) analyse the NEP’s subthemes. Limits to growth had the lowest average NEP score (8.95) and eco-crisis had the highest average NEP score (13.07). Respondents perceived climate change to be a significant threat, but were optimistic in technological innovation to avert it. Anti-anthropocentrism garnered the second highest score (11.70) with balance of nature behind (11.62) further supporting this, but without believing that humans are inherently superior to nature. The NEP and its subthemes were not correlated with support for research and deployment except eco-crisis (Table 13, Appendix B).

According to Figure 5, 51.45% (n=53) of respondents agreed that geoengineering made them think that the risks of climate change were worse than they had thought. All facets of the NEP were positively correlated with agreement except for anti-exemptionalism, indicating that those with higher environmental values might believe that geoengineering is representative of an impending climate crisis. All NEP facets were negatively correlated with agreement that scientists and policymakers have a better handle on climate change knowing that geoengineering is researched (Table 7).

| Statement | NEP facet | Significance (p) | Correlation Coefficient (rs) | Meaning |

| The prospect of geoengineering makes me think that the risks of climate change are worse than I thought | Overall | <0.001 | 0.347 | Low, positive correlation |

| Growth | 0.014 | 0.242 | Weak, positive correlation | |

| Anti-Anthropocentrism | 0.001 | 0.314 | Low, positive correlation | |

| Balance of Nature | 0.003 | 0.289 | Weak, positive correlation | |

| Anti-Exemptionalism | 0.214 | 0.124 | No correlation | |

| Eco-crisis | <0.001 | 0.340 | Low, positive correlation | |

| Knowing that geoengineering is being researched makes me think that scientists and policymakers have a better handle on tackling climate change than I thought | Overall | <0.001 | -0.364 | Low, negative correlation |

| Growth | 0.049 | -0.194 | Weak, negative correlation | |

| Anti-Anthropocentrism | 0.032 | -0.212 | Weak, negative correlation | |

| Balance of Nature | 0.010 | -0.254 | Weak, negative correlation | |

| Anti-Exemptionalism | <0.001 | -0.330 | Low, negative correlation | |

| Eco-crisis | 0.008 | -0.262 | Weak, negative correlation |

Table 7: Spearman’s Rank Order Correlation results testing the significance of environmental values on geoengineering perception statements

4. Discussion

4.1 General Perceptions

Most respondents were unfamiliar with geoengineering, and used “geoengineering” as an umbrella term to discuss potential relevant socioeconomic and sociotechnical concerns, echoing current literature (Carvalho and Riquito, 2022; Dunlop et al., 2022). Additionally, geoengineering, CDR, and SRM research were preferred to development with CDR preferred to SRM, also echoing current research (Cherry et al., 2022; Raimi, 2021). According to the open-ended questions, geoengineering’s interference with nature was not an acknowledged reason for opposition, diverging from literature arguing that people are apprehensive of geoengineering because it suggests humankind is capable of conquering nature (McDonald, 2022). Instead, one respondent noted that geoengineering does interfere with nature but has “a benevolent aim,” showing that geoengineering’s interference with nature, albeit acknowledged, might not inherently translate to opposition.

Respondents emphasised the imminence of climate change necessitating geoengineering, which suggests that participants might automatically view geoengineering as a last resort. This contributes to geoengineering’s isolation from other climate change strategies rather than its integration and is problematic as geoengineering is not meant to be a standalone solution (Fragniere et al., 2016). Some respondents noted that it was “difficult to support geoengineering without knowing [its implications]” but they “support it as a last resort if other… mitigation fails.” Respondents also expressed concern for geoengineering’s “risky” externalities and were “hesitant to support [geoengineering] without significant improvements in research.” The emphasis of acting in time implies that concern for climate change might eventually overrule concerns for geoengineering’s externalities — climate urgency could be essential in attitude formation.

4.2 The Influence of Environmental Values

Eco-crisis was weakly correlated with support for geoengineering and SRM research and deployment and CDR research. Cox et al. (2020) predicted that feelings of climate urgency might correlate with geoengineering support if there is perceived time to act, and these results affirm this. According to the open-ended questions, some believed that there is little time to act, with geoengineering being needed “before it is too late” or “as a last resort.” Concerns over geoengineering’s unknowns were dependent on climate urgency, building upon earlier links established between geoengineering support and climate catastrophe concerns.

Similarly, the only consistent environmental value influencing support for research and deployment was eco-crisis. Respondents were cognisant of geoengineering’s uncertainties and lack of definitive research, which was the most common reason for opposition, but support was justified as being necessary for human survival even if as a last resort. Moreover, there has been a move towards climate emergency “momentums” marked by events such as the UN Environment Programme ‘s 2019 emissions gap report, worldwide Strikes for Climate initiated by Greta Thunberg, and the Extinction Rebellion movement (Davidson et al., 2020). Globally, over 2,300 jurisdictions across 40 countries have declared a climate emergency, with affected populations amounting to over one billion (Aidt, 2023). Because climate emergency rhetoric has also been observed to overwhelm and disengage publics from climate action when emphasising fear and scientific authority (Bonanno et al., 2021), evidence-based insights into how climate emergency rhetoric affects public perceptions of CDR are necessary because to further understand the conditions for CDR acceptance or rejection when considering how the results of this study demonstrate that publics might view geoengineering as a last resort to solving the ongoing climate crisis.

According to the entirety of the NEP, environmental values do not consistently underpin geoengineering support due to concerns over unknown externalities except for values relating to concerns for an eco-crisis. The first objective was to investigate public perceptions of geoengineering, CDR, and SRM. Respondents generally knew little about geoengineering, CDR, and SRM, echoing current research. Some respondents explicitly stated that they support geoengineering only if other mitigation methods fail due to the lack of definitive research regarding geoengineering’s implications. There was a shared feeling that scientists and policymakers were not handling climate change as well as respondents had previously thought once learning about geoengineering. Unlike previous studies, the results of this study showed that geoengineering’s perceived interference with nature, while concerning, was not an inherent barrier for support.

The second objective was to measure environmental values through the NEP and explore its relationship with geoengineering perceptions. Respondents generally agreed with most pro-ecological items and disagreed with most anti-ecological items, and expressed more concern over an ecological catastrophe but remained optimistic that human technology will prevent said catastrophe. Respondents believed there was time to act and were thus apprehensive of geoengineering due to uncertainties around research and deployment. However, environmental values were correlated with agreement that the risks of climate change were worse than respondents had previously thought and the eco-crisis subtheme was correlated with support for research and deployment when no other subtheme was, showing that concern for geoengineering’s externalities was eventually overruled by concerns of an eco-crisis.

This provides novel evidence suggesting that environmental values through the NEP do not consistently influence geoengineering support unless relating to an eco-crisis. Instead, environmental values appear to influence how people perceive what geoengineering represents, particularly in relation to the prospect of a climate catastrophe, which eventually overrules concern for geoengineering’s unknown implications. Conclusively, this suggests that concerns for climate emergencies may be essential in attitude formation towards geoengineering.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Dr Karen Parkhill for their support and supervision of this research project, and their encouragement to submit a revised excerpt of my research project to Routes. The questionnaire used in this study received ethical approval by the University of York Environment and Geography Department’s Ethics Committee on 24 November 2022.

References

Agissova, F. and Sautkina, E., 2020. The role of personal and political values in predicting environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behavior in Kazakhstan. Frontiers in psychology, 11, p.584292.

Aidt, M., 2023. Climate emergency declarations in 2,320 jurisdictions and local governments cover 1 billion citizens.

Amburgey, J.W. and Thoman, D.B., 2012. Dimensionality of the new ecological paradigm: Issues of factor structure and measurement. Environment and Behavior, 44(2), pp.235-256.

Bonanno, A., Ennes, M., Hoey, J.A., Moberg, E., Nelson, S.M., Pletcher, N. and Tanner, R.L., 2021. Empowering hope-based climate change communication techniques for the Gulf of Maine. Elem Sci Anth, 9(1), p.00051.

Bouman, T., Steg, L. and Perlaviciute, G., 2021. From values to climate action. Current Opinion in Psychology, 42, pp.102-107.

Carvalho, A. and Riquito, M., 2022. ‘It’s just a Band-Aid!’: Public engagement with geoengineering and the politics of the climate crisis. Public Understanding of Science, 31(7), pp.903-920.

Cherry, T.L., Kroll, S., McEvoy, D.M., Campoverde, D. and Moreno-Cruz, J., 2022. Climate cooperation in the shadow of solar geoengineering: an experimental investigation of the moral hazard conjecture. Environmental Politics, pp.1-9.

Cox, E., Spence, E. and Pidgeon, N., 2020. Public perceptions of carbon dioxide removal in the United States and the United Kingdom. Nature Climate Change, 10(8), pp.744-749.

de Groot, J.I. and Thøgersen, J., 2018. Values and pro‐environmental behaviour. Environmental psychology: An introduction, pp.167-178.

Derdowski, L.A., Grahn, Å.H., Hansen, H. and Skeiseid, H., 2020. The new ecological paradigm, pro-environmental behaviour, and the moderating effects of locus of control and self-construal. Sustainability, 12(18), p.7728.

Dunlap, R.E., Van Liere, K.D., Mertig, A.G. and Jones, R.E., 2000. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: a revised NEP scale. Journal of social issues, 56(3), pp.425-442.

Dunlop, L., Rushton, E., Atkinson, L., Cornelissen, E., De Schrijver, J., Stadnyk, T., Stubbs, J., Su, C., Turkenburg-van Diepen, M., Veneu, F. and Blake, C., 2022. Youth co-authorship as public engagement with geoengineering. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 12(1), pp.60-74.

Fragniere, A. and Gardiner, S.M., 2016. Why geoengineering is not ‘Plan B’. Climate justice and geoengineering: Ethics and policy in the atmospheric anthropocene, (October), pp.15-32.

Goble, R., 2018. Examining the Enviroschools programme within the greater Wellington region: A mixed methods approach.

Hawcroft, L.J. and Milfont, T.L., 2010. The use (and abuse) of the new environmental paradigm scale over the last 30 years: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental psychology, 30(2), pp.143-158.

Kim, M.S. and Stepchenkova, S., 2020. Altruistic values and environmental knowledge as triggers of pro-environmental behavior among tourists. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(13), pp.1575-1580.

Liefländer, A.K. and Bogner, F.X., 2018. Educational impact on the relationship of environmental knowledge and attitudes. Environmental Education Research, 24(4), pp.611-624.

McDonald, M., 2022. Geoengineering, climate change and ecological security. Environmental Politics, pp.1-21.

Ntanos, S., Kyriakopoulos, G., Skordoulis, M., Chalikias, M. and Arabatzis, G., 2019. An application of the new environmental paradigm (NEP) scale in a Greek context. Energies, 12(2), p.239.

Oomen, J. and Meiske, M., 2021. Proactive and reactive geoengineering: Engineering the climate and the lithosphere. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 12(6), p.e732.

Pamplany, A., Gordijn, B. and Brereton, P., 2020. The ethics of geoengineering: a literature review. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(6), pp.3069-3119.

Raimi, K.T., 2021. Public perceptions of geoengineering. Current Opinion in Psychology, 42, pp.66-70.

Sharma, G., 2017. Pros and cons of different sampling techniques. International journal of applied research, 3(7), pp.749-752.

Tsipiras, K. and Grant, W.J., 2022. What do we mean when we talk about the moral hazard of geoengineering?. Environmental Law Review, 24(1), pp.27-44.

UK Census, 2021. Census 2021 results. [online] Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://census.gov.uk/census-2021-results [Accessed 16 Feb. 2023].

Yu, T.K., Lin, F.Y., Kao, K.Y., Chao, C.M. and Yu, T.Y., 2019. An innovative environmental citizen behavior model: Recycling intention as climate change mitigation strategies. Journal of environmental management, 247, pp.499-508.

Appendices

See PDF attached above.

#Write for Routes

Are you 6th form or undergraduate geographer?

Do you have work that you are proud of and want to share?

Submit your work to our expert team of peer reviewers who will help you take it to the next level.

Related articles