Volume 4 Issue 2

By Holly Sophia Chance, Mercia School

Citation

Chance, H. (2024) The Legacy of the Paris 2024 Olympics: A Catalyst for Sustainable Development? Routes, 4(2): 122-130.

Abstract

The question of whether the Olympics should continue to be hosted is becoming increasingly relevant considering the environmental, economic, and social challenges faced by host cities. With concerns over sustainability and the lasting impacts of such large-scale events, it is crucial to critically evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of hosting the Olympics. The influence of the Olympics extends far beyond the duration of the Games themselves as they have the power to reshape urban landscapes and stimulate economic growth. This article will use the 2024 Paris Olympics as a primary case study to explore these issues. By examining Paris’s approach to sustainability and infrastructure and considering previous Olympic events, I aim to determine if the benefits of hosting the Olympics can outweigh the significant challenges, and whether such an event can be justified in contemporary society.

1. Introduction

The International Olympic Committee’s sustainability strategy, produced in 2017, aims to add sustainability into the Olympic Games, focusing on areas like infrastructure and carbon management. As one of the longest-standing international sporting events, ensuring that the 2024 Games are sustainable is essential not only to uphold this legacy but also to set a precedent for future events. Moreover, the global visibility of the Olympics provides a unique platform to promote sustainability, showcasing how global events can be managed responsibly. Failure to address these challenges would not only undermine the credibility of the Olympics but would also miss an opportunity to influence sustainable practices worldwide. Therefore, while the scale of the event complicates sustainability efforts, it also highlights their importance, making the Paris Olympics a critical moment in the movement towards more environmentally, socially, and economically responsible global events.

It is important to consider Games which have occurred in the past to make a judgement on today’s situation and the London and Paris Olympics are to some extent relatively parallel in terms of their sustainability success—albeit measured across different timescales. The 2012 London Olympics achieved environmental sustainability, through the transformation of industrial land into the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, showing how brownfield sites were developed rather than greenfield sites, preserving habitats. However, it should be noted that urban brownfield sites around London often have greater biodiversity than some “greenfield” sites, revealing that while specific natural habitats may be protected, the spontaneous yet thriving ecosystems of these brownfield sites are frequently overlooked.

Economically, both London and Paris employed circular economy strategies to ensure long-term benefits for the local economy, rather than implementing short term developments, which would have used large quantities of non-renewable resources. However, The Rio 2016 Olympics displayed a major step back in terms of sustainability compared to both London 2012 and the Paris 2024 Games despite the environmental sustainability efforts of Paris being undermined by pollution in the Seine, where pollution levels were over 1.7 million times the level considered hazardous. Data from water utility company Eau de Paris obtained by Politico (Roush,2024) showed that the water quality was not safe to swim on most days during the Olympics and was of questionable quality on the day of the mixed relay triathlon. Furthermore, Rio was left with approximately $13 billion debt, and new developments, such as the Olympic Park, fell into disrepair within months of the event, encouraging vandalism as residents no longer felt a sense of place attachment. The Rio Games has highlighted the challenges of hosting sporting events without effective sustainability measures, serving as an initiative for future host cities to act more responsibly.

2. The Impacts on Paris’ Infrastructure

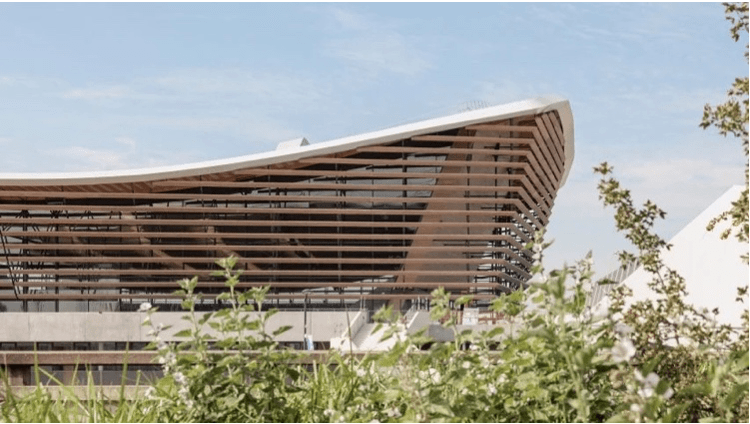

In the wake of the Olympics, it is expected that Paris will experience many positive impacts that extend far beyond the closing ceremonies. Repurposed sports venues and newly constructed facilities provide opportunities for ongoing athletic and recreational activities, promoting a healthy lifestyle. An example is the Aquatics Centre, which has been built with environmental sustainability in mind. For example, it has solar panels on the roof, making it “one of the biggest solar farms in France”, with solar energy expected to generate 20% of all required electricity for the building. This shows that the sustainability of the event has been considered because less fossil fuels will need to be burned to power the locations which are being used in the Olympics. This forms part of a wider strategy for “90% of the needed energy to be provided with renewable or recovered energy”, according to the building’s architects (Dezeen, 2023). For example, figure 1 shows The Aquatics Centre which can accommodate 5,000 spectators with all its seats made of recycled plastics. The landscape design includes 100 trees and shrubs, intended to help improve air quality in the area while encouraging more biodiversity at the site. This is because the capacity of the local carbon sink will be increased as there is more vegetation which is able to remove harmful gases from the atmosphere.

Figure 1: shows the Aquatics Centre: the only permanent building constructed for The Paris Olympics]. Source: https://www.dezeen.com/2024/04/04/timber-aquatics-centre-paris-2024-olympic-games/#:~:text=Located%20in%20the%20Saint%2DDenis,begins%20on%2026%20July%202024

Furthermore, Paris authorities debated whether to inspect the balconies of thousands of buildings along the river Seine because of warnings that they could collapse under the weight of spectators watching the opening ceremony. “It’s clearly a scenario that could happen,” Olivier Princivalle of the property professionals’ association FNAIM told Agence France-Presse in 2023. “We absolutely have to be sure that balconies will support the extra weight, and that balustrades are solidly attached, to avoid incidents”. Buildings often 150 years old or more “may not be up to the additional strain”, he said (Dezeen, 2023). Balconies on Parisian buildings from the late 19th-century would support 350kg/m2, the equivalent of about three adults. However, the lack of sustainability in maintaining these structures highlights a broader issue of urban decay, disproportionately affecting different communities relative to their wealth. Affluent neighbourhoods along the Seine are more likely to have the resources to renovate and reinforce their balconies, ensuring the safety of both residents and tourists. In contrast, less wealthy areas might struggle to afford the maintenance, leading to a higher risk of structural failures. This disparity shows the need for equal investment in urban sustainability to protect all communities, ensuring that the city’s reputation does not come at the expense of public safety and social equity during the Olympics.

3. Environmental Sustainability

While the Paris 2024 Olympics promised numerous benefits for the city into the future, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential environmental disadvantages associated with hosting such a large-scale event. Often, the environmental benefits or credentials of a company, or in this case an event, are used to persuade the public that their products are environmentally friendly. This is known as greenwashing, which refers to the practice of promoting an event as eco-friendly while failing to make substantial environmental improvements. This was particularly an issue in the Rio Olympics in 2016, where at Guanabara Bay there was aimed to be more than 80% of overall sewage collected and treated by 2016 (Rio, 2016). But as the Games approached, it was obvious these projects were not on track as nearly 40 tons of dead fish turned up at Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas in April 2015.

As a result, the Paris Olympics was under significant pressure to uphold its legacy. The Games were held across 16 different cities in France, attracting 10,714 Olympic athletes and 15 million spectators. The construction and infrastructure projects required to accommodate the Games lead to increased carbon emissions, habitat destruction, and waste generation. The development of Olympic venues, moreover, destroyed local natural habitats which, in turn, disrupted local ecosystems and biodiversity, meaning that the event may no longer be considered sustainable because the ecosystems will not be preserved for future generations to enjoy.

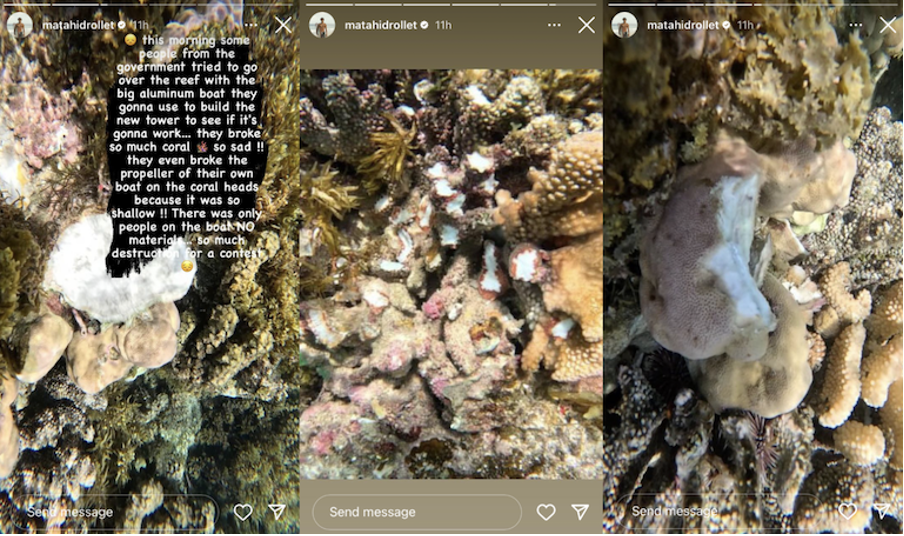

An example of this is in Tahiti, where the Olympic surfing event was held. There were discussions with the Paris 2024 Olympic Committee for months over the environmental impacts of the event venue construction in the town and bay of Teahupo’o. Early in 2024, the Olympic Committee released plans for the $5 million aluminium tower, to be built in place of an existing wooden tower. The committee claimed that the tower would be built in an area with fewer corals and cuttings would be taken to ensure they can regrow (Seal,2023). As a result, the Olympic Committee made a final decision to continue with the building of the new aluminium tower, with some modifications, despite backlash from the public. The surface area of the tower is 25% smaller than the original plans, making it the same size as the existing wooden tower. The weight of the new tower is nine tons – instead of the original 14 tons – to reduce the load on the foundations and it was installed on the same site as the old wooden tower. This was seen as an advantage because the tower could serve as a symbol of eco-friendly innovation. Figure 2 highlights the importance of repurposing or recycling the structure after the Olympics to mitigate the coral reef being damaged, demonstrating a commitment to sustainability after the event has finished.

Figure 2: Screenshots of Matahai Drollet’s December 1, 2023, Instagram story depicting damage to the coral reef caused by the barge.

Furthermore, the event served as a promoter for improving public transport, encouraging the use of electric vehicles, and enhancing pedestrian-friendly spaces, reducing both air pollution and traffic congestion in the long term. This is because the Games have been described as the greenest in Olympics history, with Paris 2024 pledging to halve the event’s carbon footprint compared to the average of previous Summer Games. However, aiming for the target of 1.75 million tonnes of CO2 (Euromonitor, 2024) should be scrutinised as it may not be based on a thorough assessment of potential emissions but rather a symbolic goal. This target may be overly optimistic with the innovations implemented not have lasting benefits and influence on future events. Previous summer Olympics, which include Tokyo 2020, Rio 2016, and London 2012, have emitted an average of 3.5 million tonnes of CO2 (Goransson, 2023). Having less emissions than Tokyo’s Games will be particularly difficult as that event did not have spectators due to COVID-19, meaning that there were limited amounts of pollution due to less tourism.

4. Socio-economic Sustainability

Socially, one significant concern revolves around the potential for socio-economic inequalities to be exacerbated. The investments in infrastructure and venue construction will prioritise certain areas, leaving others lacking new development. Some local hotels and restaurants struggled as they were overshadowed by larger, international hotel chains and venues catering to the influx of tourists. For example, average prices for the week starting July 22nd in larger chain hotels came in at $629 per night for a 4-star hotel (Fox, 2024). This concentrated profits within large, international hotel chains, resulting in less economic benefit for the local economy. The disappearance of these small businesses eroded the cultural history of Paris, which is a key draw for tourists. This shift could have long-term implications, making the city less attractive to visitors who prefer authentic experiences.

When politicians promote hosting the Olympics, they often mention job opportunities, particularly in the construction and hospitality sectors. The Paris 2024 organising committee claimed that the event would be “a lever for boosting activity and employment”, thanks to “over 181,000 jobs mobilised”. It specified that this figure included jobs specifically created for the occasion, and jobs that will be involved in the Olympics in some way, but already exist. To take place in the best conditions, Olympic committees also rely heavily on 45,000 volunteers who are, by definition, not paid.

Relying solely on volunteers for the 2024 Paris Olympics could have mixed consequences on the sustainability of the project. On the positive side for the profit-driven Olympics, volunteers reduce the overall cost of the event, which can free up resources to be allocated toward sustainable initiatives such as eco-friendly infrastructure and renewable energy sources. However, the reliance on volunteers can pose challenges due to trade-offs. Volunteers may lack the professional training required for efficient and effective management of sustainability initiatives, such as waste management for Veolia and conserving energy with Acciona Energía. Moreover, there is a risk that wealthier individuals could benefit more easily from the opportunity to volunteer, potentially exacerbating inequalities. This reliance might overshadow the need for paid positions that could offer stable employment. Therefore, it is essential to complement their efforts with training to ensure that the sustainability objectives are fully met.

Economically, the substantial investments, including infrastructure upgrades and venue construction, often come with large price tags that can strain public budgets and divert funds from other essential services and projects. This has caused the French government to fall into an even larger budget deficit compared to what it had previously. For example, the projected budget for the Paris 2024 Olympics has risen from £3.41 billion at the end of 2021 to £3.78 billion at the end of 2022 (Rowbottom, 2022). In fact, the estimated total cost of hosting the 2024 Olympics was around $8.2 billion, which would make these the sixth most expensive Olympic Games of all time. Including Paris, five of the past six Olympics had inflation-adjusted cost overruns of well more than 100 per cent, according to a University of Oxford study (Budzier, 2024), exemplifying how although there are efforts to make the Games economically sustainable, the target has not yet been reached. Some economists and researchers argue that a truly sustainable Olympics will need to look a lot different than the Games we know today, if the budget was to be minimised.

In addition, although factors like tourism will increase the amount of short-term revenue, there are concerns about the long-term financial implications of hosting the Olympic Games. London, Beijing, and Salt Lake City all saw decreases in tourism the years of their Olympics. Olympic tourists will largely replace other tourists that would have come anyway. In London, for example, studies found that there were fewer tourists in the city during the Olympic Games in 2012 than during previous summers (Urvoy, 2024). For Paris, a city heavily economically reliant on tourism, this post-event decline could result in financial strain on businesses and reduced revenue from tourism-related activities. This potential downturn connotes the significance for Paris to create sustainable tourism growth, including long-term planning to ensure that the benefits of hosting the Olympics extend beyond the event itself, such as by enhancing the city’s image through improved infrastructure that continue to draw visitors. Failure to address these concerns could result in economic disparities, particularly affecting smaller businesses and communities dependent on steady tourist flows.

The pollution of the Seine River during the Paris Olympics presents a critical obstacle to the city’s ambitions of fostering sustainable tourism growth. Historically, the Seine has suffered from extensive pollution due to decades of industrial waste and runoff from urban areas. The high levels of bacteria and other pollutants in the river not only pose health risks to athletes but also tarnish the image of Paris as a leader in sustainable tourism. Furthermore, the visibility of this problem during a globally watched event like the Olympics could stimulate negative perceptions and present Paris as an unsustainable destination. This highlights the challenge of balancing economic development with environmental protection and stresses the need for more effective measures to restore natural resources like the Seine.

Another issue is that many Parisians were shocked by the fact that transport fares doubled for the duration of the event with single metro tickets rising from €2.10 to €4. This meant that Parisians were expected to work from home to free up seats on overcrowded metros and buses. This acted as a catalyst for rising disparity between different social classes, as domestic workers were to be only able to access their offices if they were receiving a higher income. However, this was not a huge concern for the people of Paris as shortly after the event, prices fell again, allowing an increase in the commuting capacity to their original workspaces. But in the future, it is important to consider that there may be a slight permanent rise in the price of public goods, such as transport, to ensure that the government can raise revenue so that they can continue to pay off the debt created from hosting such a large event, creating concerns for certain members of the community.

5. Conclusion

Whilst the sustainability goals of the 2024 Paris Olympics are somewhat successful, their implementation faces significant challenges to all stakeholders involved. The historical significance and global visibility of the Olympics offers a large platform to show sustainable practices, but this will increase the amount of pressure that Paris faces to ensure that they hit the three pillars of sustainability: social, economic, and environmental sustainability. Local stakeholders, including Parisian residents and businesses, will have to ensure that the Paris Olympics does not follow the pattern of previous host cities that experienced a post-event decline in tourism and economic activity. Moreover, tourists must also be engaged in these efforts, promoting responsible behaviour and consideration of their own carbon footprints. Without the involvement of these stakeholders, the sustainability goals of the Paris Olympics risk becoming non-existent. Ultimately, it is imperative that all players involved address these challenges, ensuring that the event has a legacy of lasting environmental and social impact.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to several individuals who supported me in the completion of this article. My thanks go to Mr Dunn, Miss Murphy, and Mr Ridler for being exceptional teachers and for their invaluable encouragement and support throughout A- levels. I am also grateful for Miss Lever and Mr Ridler for checking my work and providing insightful feedback. Lastly, I would like to thank Miss Heritage for always believing in my abilities and inspiring me to strive for excellence, greatly improving my confidence.

References

Boykoff, J. and Mascarenhas, G. (2016) The Olympics, Sustainability, and Greenwashing: The Rio 2016 Summer Games, Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27:2, 1-11, DOI: 10.1080/10455752.2016.1179473.

Budzier, A. and Flyvbjerg, B. (2024). The Oxford Olympics Study 2024: Are Cost and Cost Overrun at the Games Coming Down?.

Dezeen. (2024). Timber Aquatics Centre completes in Paris for 2024 Olympic Games. [online] Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2024/04/04/timber-aquatics-centre-paris-2024-olympic-games/#:~:text=Located%20in%20the%20Saint%2DDenis [Accessed 6 Apr. 2024].

Euromonitor. (2023). Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Challenges and Opportunities for…. [online] Available at: https://www.euromonitor.com/article/paris-2024-olympic-games-challenges-and-opportunities-for-french-tourism [Accessed 6 Apr. 2024].

Mongabay Environmental News. (2023). Reef damage from 2024 Olympics surfing venue is avoidable (commentary). [online] Available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2023/12/reef-damage-from-2024-olympics-surfing-venue-is-avoidable-commentary/ [Accessed 7 Apr. 2024].

Roush, T. (2024). Paris Mayor Swims In Seine Amid Pollution Concerns—Here’s Why Olympic Events Could Be Canceled. [online] Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/tylerroush/2024/07/17/paris-mayor-swims-in-seine-amid-pollution-concerns-heres-why-olympic-events-could-be-canceled/ [Accessed 12 Aug. 2024].

http://www.insidethegames.biz. (2022). Paris 2024 budget rises to €4.38 billion due to inflation and added expenses. [online] Available at: https://www.insidethegames.biz/articles/1131248/paris-2024-revised-budget-increase [Accessed 7 Apr. 2024].

2024, P.O. (2023). Paris 2024. Available at: Olympics.com [Accessed 2 Apr. 2024].

#Write for Routes

Are you 6th form or undergraduate geographer?

Do you have work that you are proud of and want to share?

Submit your work to our expert team of peer reviewers who will help you take it to the next level.

Related articles