Volume 4 Issue 1

By Zuhri James, University of Cambridge

Citation

James, Z. (2024) Exploring the construction of Arctic imaginaries within the spaces of the museum. Routes, 4(1): 50-65.

Abstract

Museums have long been central to the construction, circulation and (re)production of Eurocentric imaginaries. The University of Cambridge’s Scott Polar Research Institute which serves as both a museum and a site of contemporary polar research is no different. Turning to the Institute’s ‘Exploration and Encounter’ museum display, this paper explores how museums continue to operate as bastions of colonialism which consolidate celebratory narratives of British empire. I conclude by reflecting on the potential avenues for further research.

1. Introduction

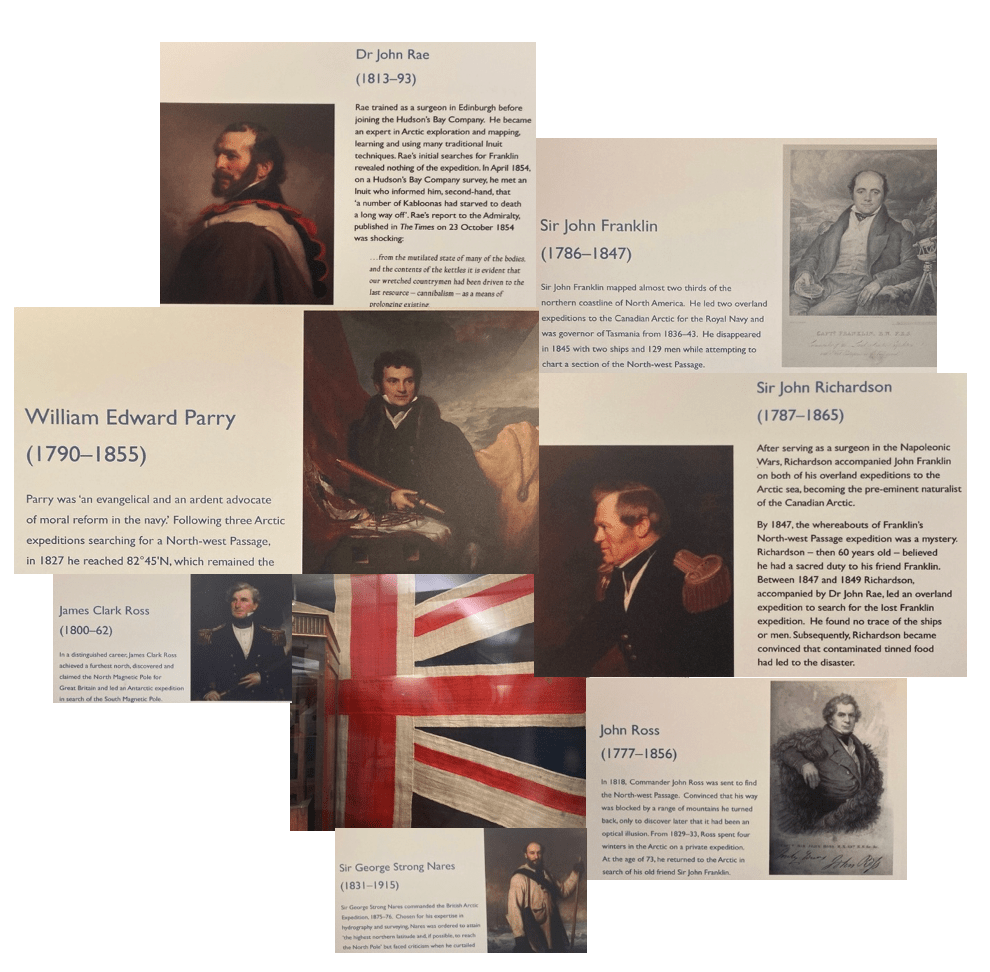

Weaving in and out of the Scott Polar Research Institute’s [SPRI] dense conglomeration of visitors, staff and exhibits, I stop at the ‘Exploration and Encounter’ display and glance up at the mélange of knighted names and associated portraits – ‘Sir John Franklin… Sir John Richardson…’ [Fig.1]. Slowly it dawns on me, albeit registering at the very edges of effability, that the display constitutes a kind of celebratory temple of whiteness. Swords, telescopes and other historical memorabilia enchant onlookers. ‘The Arctic is a perilous, otherworldly place’ one visitor remarks to his son. ‘It still is: people still die there each year.’ As he draws himself closer to the display, further narrativising to his son this Northern region of the seemingly abject, his emotive contours of repugnance and fascination begin to blur, eventually reaching the point of indistinction. (Field diary 11 April 2023)

Figure 1: The SPRI’s Exploration and Encounter display. Source: Author.

Walking back from my visit to the SPRI, I cogitated upon the vignette above: evoking my experience of traversing its internal museumscape where portrayals of ‘worthy, adventurous and devoted men… [that] nibbled at the edge… conquering a bit of truth here and a bit of truth there’ (Conrad, 1924: 254) reverberated with echoic force. Signalling the ‘imposition of British masculine energies on the Arctic’ (Miller, 2017: 121), these depictions betray an inert, didactic neutrality which is routinely ascribed to museums (Lowenthal, 1993; Lidchi, 1997; Bennett, 2005; Camarena, 2006; Geoghegan, 2010). Yet museums have never been sites of impartiality. Created by the dominant classes of eighteenth-century Europe and their dispossessive acts of looting and subjugating cultural artefacts, human remains and diverse knowledge systems, museums have long been undergirded by stratified hierarchies of humanness.

Critically, museums still operate as ideologically contorted institutions. Undergirded by western classification systems and curatorship practices oriented around European ways of labelling and framing ‘other’ cultures, museums continue to function as theatres of pain which foment intensely dysphoric feelings for racialised communities whose cultural histories are incessantly misrepresented by imperial taxonomies and narrative systems (Tolia-Kelly, 2016). Here, coloniality – taken as the splintering geometries of power that emanated out of colonialism and have now interlocked with modernity itself (Quijano, 2000; Escobar, 2007; Radcliffe, 2017) – is ‘a presence that is all-saturating, overflowing, ever-present’ (Edwards, 2018: np).

This paper explores this critical intersection between museums and coloniality by turning to the SPRI’s Exploration and Encounter display which revolves around British exploratory histories across the Northwest Passage (the sea lane between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans). Founded by the first Professor of Geography at the University of Cambridge Frank Debenham, who initially intended for it to house a comprehensive library of polar literatures, maps and rooms for researchers as well as a museum displaying the equipment used by European explorers, the SPRI emerged as a centre which sought to unify scientists, researchers and resources for the betterment of circumpolar expeditions (Debenham, 1921; Stoddart, 1989). Fundamentally, it also served as a kind of cenotaph for Captain R.F. Scott and his fellow voyagers who in 1912 perished in Antarctica, leading Connelly and Warrior (2019: 262) to contend that since its inauguration, the SPRI has “perpetuated a particular kind of history, focused on memorializing individuals’ achievements”. Yet the valorization of British exploration within the spaces of the museum evokes various tensions. Is there not a risk, for instance, that memorialization lapses into a kind of hagiographic lionization of British polar histories? When objects such as survey instruments and items of clothing are displayed to evoke historical tales of British heroism, is there not a danger of implicitly off-staging Indigenous histories and epistemologies? Which is to ask, what are the politics of representation at work within the SPRI?

2. Imaginative geographies

Before turning to an analysis of the SPRI’s Exploration and Encounter display, it is useful to first construct a theoretical framework apt for interrogating the confluence of narrative, geography, and the imagination. The Palestinian-American postcolonial literary critic Edward Said’s (1978) work on Orientalism provides us with one possible starting point for such a task. For Said (1978), the relationship between the West and East had long been mediated by the former’s construction and deployment of imaginative geographies which narrativised the latter as a pathological place of bestial and exotic beings positioned ‘outside of modernity’ (Tolia-Kelly and Raymond, 2020: 7). Sustaining a kind of epistemic domination interlaced with broader attempts to ‘cajole, conquer, civilize, consume, conserve and capitalize upon’ (Stuhl, 2013: 94) the so-called Eastern creeping danger, these imaginative geographies were not mere literary inaccuracies but rather, constituted highly fractured, asymmetric systems of power (Gregory, 2004). Systems which continue to pervasively furnish the identity of the Western world as a disciplined and progressive space whilst the Eastern orient is perpetually codified as its barbaric, delinquent antipode. Building on Said’s theoretical foundations, scholars across the environmental humanities have recently mobilised the neologism ‘Arcticism’ to denote epistemically violent imaginaries of the Arctic and its peoples:

Typically, the Arctic is imagined as either an icy hell or an inhabitable paradise… to be enjoyed at a distance… such images become a consolidated, self-perpetuating vision, an “Arcticism.” (Ryall et al., 2010: x)

Woven into literary genres, television, and institutional spaces such as the museum, these Arcticist imaginaries – reducing the region to a strange, otherworldly region inhabited by the homogenised figure of the Indigenous ‘other’ (Bravo and Sörlin, 2002; Friesen, 2005; Lahtinen, 2020) – remain pervasive. The sheer scale, for instance, at which the region’s geographical complexities have been displaced by speculative media rhetorics dramatising the opening of shipping lanes and, relatedly, untapped natural resources, has notably intensified in recent years (Jørgensen and Sörlin, 2013; Powell and Dodds, 2010, 2014). Not only do these Arcticist tendencies trivialise the geographies of the Arctic, however, spectacularizing its geopolitics, they also reduce the region to a site of Euro-American potentialities, obfuscating how it is a place where Indigenous peoples and endangered animals go about the motions of everyday living on a damaged plant (Cameron, 2015; Dodds and Nutall, 2019). We might flag here how processes such as polar amplification – which refers to a disproportionate heating up of the poles relative to planetary averages – are routinely elided within regnant Arcticist imaginaries, as are the differentiated consequences these intensifying changes are having for Indigenous peoples and other-than-human geographies across the region (Chartier et al., 2021; Ridanpää, 2007; Reid, 2019; Toivanen, 2019). Indeed, it is these discursively violent Arcticist imaginaries which I now turn to vis-à-vis the SPRI’s Exploration and Encounter display.

3. Arcticist imaginaries within the SPRI

Figure 2: A word cloud displaying the language used across the SPRI’s ‘Exploration and Encounter’ display. Source: Author.

If, as Davidson notes, the Arctic has historically occupied a central space within the western imagination ‘as a man’s world… [that is] “no place for women”’ (2005: 76), then the SPRI’s Exploration and Encounter display can be seen as something of a paradigmatic generator of these Arcticist narratives shrouded in masculinist adventure (Dittmer et al., 2011; McCannon, 1997; Medby and Dittmer, 2021). Neo-Mackinderian descriptions describing ‘pre-eminent, ‘distinguished’ heroic men who objectively ‘mapped’ ‘explored’ and ‘discovered’ a region that was, prior to British arrival, seemingly nothing but an ‘unexplored’ realm of ‘harsh weather’ and ‘intense cold’ (Fig.1; Fig.2; Fig.3; Appendix.1; 2) reverberate across the display evoking a very specific – almost didactic – symbolism. Not only was the Arctic void of life and full of promise (Ray and Maier, 2017), but this was an untapped potentiality within an otherwise barren and desolate region which required British explorers ‘with an imperial eye… so that its resistant foreignness could be “understood”, tamed, mastered and domesticated’ (Chaturvedi, 2019: 445).

Figure 3: A photomontage of historical Arctic explorers who form a significant part of SPRI’s ‘Exploration and Encounter’ display. Source: Author.

These textual narratives valorising the ‘explorer-hero… white, imperial male’ (Ryall et al., 2010: x) are only further augmented by the gendered and racialised undercurrents flowing through the display’s evocative imagery. Consider, for instance, the photomontage above. Revering in the lives and feats of historically eminent, white British male explorers, this constellation of portraits animates a kind of aesthetics of Eurocentric domination; one which implicitly venerates the imposition of masculinity over so-called monstrous and climatically hostile terrains (Miller, 2017). The distinctions between the Arctic as a region in its own rightand one which was, prior to British arrival, a ‘vulnerable and feminised wilderness… awaiting… penetration by (male) explorers’ (Bruun and Medby, 2014: 916) are thus blurred: this was a pathological realm idly waiting to be discovered, disciplined, and put to work by European voyages of scientific exploration.

Yet there are good reasons to be wary of this propagation of conceited narratives which enrol museum viewers into interventionist saviour ideologies and imperialist ways of seeing (Alpers, 1991; Miller and Wilson, 2022), not least because by discursively flattening the Arctic to an economically fecund playground for grandeur performances of masculinist fantasy, the area’s geographical complexities remain largely eclipsed by idolatry rhetorics of white exploration (Fleming, 2011; Fjellestad, 2016). Moreover, when the Arctic is narrativised as a climatically hostile terrain that the British were seemingly entitled to, not only is a semantic field frustratingly detached from the histories of colonial conquest perpetuated, but the logics of terra nullius – which initially falsified the region as an empty conduit upon which a chauvinistic whiteness could be inscribed – remain entirely concealed (Hulan, 2002; Bowden, 2011; Hanrahan, 2017; Kodó, 2023).

Along these lines, it is difficult to overestimate how the display’s underlying valorisation of the British male explorer as some kind of Herculean conqueror of nature is a manoeuvre only made possible through the ‘invisibilization of Indigenous peoples’ (Tam et al., 2021: 5). In the case of the SPRI’s Exploration and Encounter display, which is oriented around the histories of the Northwest Passage, this is disturbing not least because of ‘the critical role [that] Inuit and other indigenous peoples… played in the exploration of the Northwest passage’ (Hatfield, 2015: np). Not only, for instance, were the Inuit the initial discovers and explorers of the Northwest passage, but their capacities to settle across its polar landscapes, as Alfred ER Jakobsen (2018: 32) has recently written within a multi-authored Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami publication, were fundamentally ‘because our ancestors were the only human beings who had the physical strength, spiritual powers, and engineering abilities to be able to build igloos from snow’, and relatedly, find ways to co-exist with ‘some of the biggest marine mammals like humpback whale[s] and the bowhead’ (ibid; cf. Sakakibara, 2010).

Foregrounding the historicity of these self-determined Indigenous accounts, one is left wondering how the display’s pervasive evocation of European superiority withstands. Indeed, this Eurocentric persistence only grows increasingly peculiar when considered against our contemporary socio-political juncture where increasingly vociferous calls for decolonisation are demanding that museums resist romanticised reproductions of imperial consciousness by allowing for ‘multivalent voices and multiauthorial possibilities to emerge and strengthen, in documenting and curating… complex and specific histories’ (Vawda, 2019: 78); a timely insistence on decolonial polyvocality which it appears, has not yet registered within the white walls of the SPRI’s Exploration and Encounter Display. What we have in the case of the SPRI’s Exploration and Encounter display, then, is an agglomeration of anaesthetized facts evacuated of critical self-reflexive content, which fail to find ‘the delicate balance between lessening the reliance on heroic narratives as contemporary historiography demands, or at least making such narratives more nuanced and complex [by] challenging the blank, isolated and remote imagery’ (Connelly and Warrior, 2019: 272) so often attached to the Arctic.

Upon further historical reflection, however, perhaps these racialised representations which reverberate across the SPRI are not so surprising. In 2022, for instance, The University of Cambridge’s ‘Advisory Group on Legacies of Enslavement’ report revealed the university’s historical entanglements with enslavement (University of Cambridge, 2022). Whether it was families connected to the slave trade who sent their children to Cambridge to further their social prestige; the colleges who financed their everyday operations through investments in corporations that were connected to colonialism; or the various Cambridge intellectuals who defended slavery on the basis that enforced labour was ultimately a force for societal good, Cambridge has long had an uneasy relationship to the histories of colonial exploitation (Chae and Tabassum, 2018). Perhaps here, we can trace something of an ideological continuity between Cambridge’s institutional embedment within slavery and Frank Debenham’s initial visions for a Polar Institute that would honour the work and lives of “budding explorers” (1919: np) who, as this paper has revealed, fed into what the historical geographer Felix Driver (1999) calls geography militant: voyages of colonial exploration that were propelled by the insatiable search for total knowledge of the earth.

It is important to recognise, however, that the SPRI is beginning to reconfigure these histories. A wealth of output from critical scholars within the institute, ranging from the architect and urbanist Morgan Ip’s (2015) work on the importance of participatory mapping in the co-design of the Future North, to the cultural, historical and political geographer Richard’s Powell’s (2023) work on the intersections between Arctic exploration and colonial power, suggests the very fabric of the institute is beginning to radically dismantle its coloniality-modernity nexus. And whilst the institute’s ongoing decolonial endeavours remain confined “to a very limited extent” (Peers et al., 2020: 1), it has noted it is increasingly acquiring material from Indigenous writers with the aim of formalising a new collections policy that foregrounds self-determined Indigenous accounts and thus a new kind of “knowledge repatriation” (ibid: 2), in line with broader attempts to decolonise Geography at Cambridge (Geography Department, 2021). Alongside this, the institute have also recognised their existing classification system, last updated in 1994, carries “offensive connotations for the indigenous communities of the Arctic” (Peers et al., 2020: 2), which they are hoping to remediate by actively consulting with members of various Indigenous communities situated across the Arctic.

In many ways, the institute’s recognition that these decolonial processes are “likely to take some time” (ibid: 2) is promising for decolonisation is inherently processual, involving an iterative undoing and delinking of coloniality from modernity: a continual reassessment of our situated positionalities and the spaces we occupy and produce (Mignolo and Walsh, 2018; Radcliffe, 2022). What these nascent decolonial manoeuvres point to, then, are perhaps the contours of a new and revitalised SPRI that will potentially rupture rather than reinforce, the historical orderings and mutations of colonialism that inhere within the spaces of the museum.

4. Conclusion

This paper has illuminated how the SPRI’s Exploration and Encounter display is distorted by neo-romanticist mythifications of the Arctic (Bravo, 2019; Chartier, 2022). Concomitant with discursive valorisations of British exploratory histories and the obfuscation of Indigenous ontologies, these resounding Arcticist narrations emblematise how museums continue to operate as bastions of colonialism (Frost, 2019) pervaded by ‘celebratory narratives, art-historical perspectives [and] de-historicised ethnographic descriptions’ (Giblin et al., 2019: 474). Constrained by a focus on representation, however, the paper has not explored how the display’s epistemically unjust narratorly impositions intersect with questions of affect. Continued research, then, following the cultural geographer Divya Tolia-Kelly’s (2019) recent work, could investigate how Eurocentric imaginaries, rather than merely operating as static texts to be read, affectively resonate with different bodies across contemporary museumscapes.

How might considering, for instance, the feelings of alienation effectuated by museums, re-orient our analytical vantage point away from still-pervasive disciplinary fixations on representation and textuality ‘frozen by “discourse”’ (Saldanha, 2007: 9) towards more embodied conceptualisations of museums as racially exclusionary theatres of pain which affectively materialise within asymmetric geometries of power? If ‘representations of reality can have powerful [a]ffects’ (Waterton and Smith, 2010: 7), what kind of experiential lines are these operative across within the spaces of the museum? Such research would have to intersectionally attune to the ways that communities experiencing heritage spaces as alienating ones, are not homogenous entities with identical angles of arrival (Ahmed, 2010), but variegated collectives whose racialised identities are often intertwined with racial and gendered differences.

5. Appendix

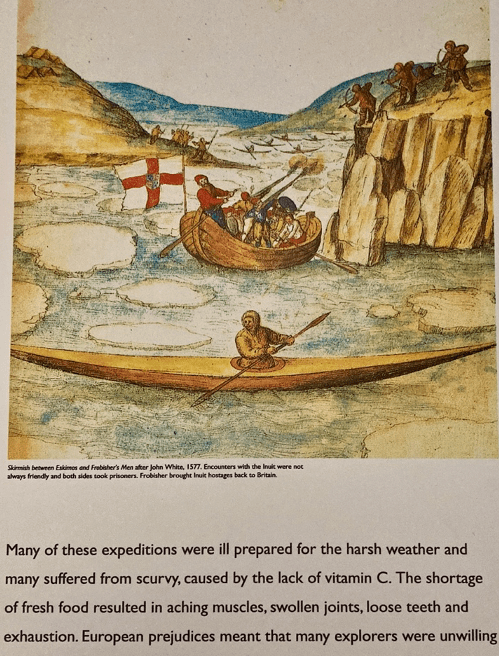

Appendix 1: An image from the display emblematising the discursive ‘othering’ of the Arctic through descriptions of otherworldly climatic conditions. Source: Author.

Appendix 2: An image from the display taken from the section on William Edward Parry which further contributes to the display’s discursive ‘othering’ of the region. Source: Author.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank Olga Petri for her insightful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

References

Ahmed, S. 2010. The promise of happiness. In The Promise of Happiness. Duke University Press.

Alpers S. 1991. The museum as a way of seeing. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display (pp. 25–32).

Bennett, T. 2005. Civic laboratories: Museums, cultural objecthood and the governance of the social. Cultural studies, 19(5): 521-547.

Bowden, B. 2011. The thin ice of civilization. Alternatives, 36(2): 118-135.

Bravo, M. 2019. North Pole: nature and culture. Reaktion Books.

Bravo, M. and Sörlin, S. (Eds.) 2002. Narrating the Arctic: a cultural history of Nordic scientific practices. Science History Publications/USA.

Bruun, J.M. and Medby, I.A. 2014. Theorising the thaw: Geopolitics in a changing Arctic. Geography Compass, 8(12): 915-929.

Camarena, C. 2006. Community museums and global connections: The union of community museums of Oaxaca. In Museum Frictions (pp. 322-344). Duke University Press.

Cameron, E. 2015. Far off Metal River: Inuit lands, settler stories, and the making of the contemporary Arctic. UBC Press.

Chae, H. and Tabassum, F. 2018. What is decolonisation and why does it matter at Cambridge? [online] Available at: https://www.varsity.co.uk/features/16143 [Last Accessed 17 April 2024]

Chartier, D. 2022. L’imaginaire du Nord est-il genré? Regard statistique, lieux communs, figures et représentations. Nordic Journal of Francophone Studies/Revue nordique des études francophones, 5(1).

Chartier, D., Lund, K.A. and Jóhannesson, G.T. 2021. Darkness. The Dynamics of Darkness in the North. Montréal and Reykjavik: Imaginaire Nord and University of Iceland,” Isberg” series.

Chaturvedi, S., 2019. Arctic geopolitics then and now. In The Arctic (pp. 441-458). Routledge.

Connelly, C. and Warrior, C. 2019. Survey stories in the history of British polar exploration: museums, objects and people. Notes and Records: the Royal Society journal of the history of science, 73(2): 259-274.

Conrad, J. 1924. Geography and some explorers. National Geographic, 45(3): 239-274.

Davidson, P. 2005. The idea of north. Reaktion Books.

Debenham, F. 1919. Letter to ‘Mrs Bill’ (Oriana Wilson, widow of Edward A. Wilson, who perished with Robert F. Scott), Cambridge, 26 October 1919, Scott Polar Research Institute, MSS in ‘Working files, SPRI history, inception’.

Debenham, F. 1921. The future of polar exploration. The Geographical Journal, 57(3): 182-200.

Di Palma, V. 2014. Wasteland: A history. Yale University Press.

Dittmer, J., Moisio, S., Ingram, A. and Dodds, K. 2011. Have you heard the one about the disappearing ice? Recasting Arctic geopolitics. Political Geography, 30(4): 202-214.

Dodds, K. and Nuttall, M. 2019. The Arctic: What everyone needs to know®. Oxford University Press.

Driver, F. 1999. Geography militant : cultures of exploration in the age of empire. Oxford: Blackwell.

Edwards, E. 2018. Addressing colonial narratives in museums. [online] Available at: https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/blog/addressing-colonial-narratives-museums/ [Last Accessed 7 October 2023]

Escobar, A. 2007. Worlds and knowledges otherwise: The Latin American modernity/coloniality research program. Cultural studies, 21(2-3): 179-210.

Fleming, F. 2011. Ninety degrees north: The quest for the North Pole. Granta Books.

Fjellestad, M.T. 2016. Picturing the Arctic. Polar Geography, 39(4): 228-238.

Friesen, T.M. 2005. The Last Imaginary Place: A Human History of the Arctic World.

Frost, S. 2019. ‘A Bastion of Colonialism’ Public Perceptions of the British Museum and its Relationship to Empire. Third Text, 33(4-5): 487-499.

Geoghegan, H. 2010. Museum geography: Exploring museums, collections and museum practice in the UK. Geography Compass, 4(10): 1462-1476.

Geography Department., 2021. Decolonising Cambridge Geography. [online] Available at: https://www.geog.cam.ac.uk/about/decolonisation/#:~:text=Decolonising%20involves%20recognising%20that%20colonial,in%20teaching%2C%20learning%20and%20research. [Last Accessed 17 April 2024]

Giblin, J., Ramos, I. and Grout, N. 2019. Dismantling the master’s house: thoughts on representing empire and decolonising museums and public spaces in practice an introduction. Third Text, 33(4-5): 471-486.

Gregory, D. 2004. The Colonial Present: Afghanistan. Palestine. Iraq. John Wiley & Sons.

Hanrahan, M. 2017. Enduring polar explorers’ Arctic imaginaries and the promotion of neoliberalism and colonialism in modern Greenland. Polar Geography, 40(2): 102-120.

Hatfield, P. 2015. Perspectives on the Passage: encountering the explorers. [online] Available at: https://blogs.bl.uk/americas/2015/02/perspectives-on-the-passage-encountering-the-explorers.html [Last Accessed 25 April 2023]

Hulan, R. 2002. Northern experience and the myths of Canadian culture (Vol. 29). McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

Ip, M. 2015. Participatory Mapping in the Co-Design of the Future North, pp.343-352.

Jakobsen, ERA. 2018. “Inuit need to be at the negotiating table on the Northwest Passage” in Inuit Perspectives on the Northwest Passage Shipping and Marine Issues. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, p. 32-34.

Jørgensen, D. and Sörlin, S. (Eds.) 2013. Northscapes: History, technology, and the making of northern environments. UBC Press.

Kodó, K. 2023. Local and Universal: The Canadian Inuit and the Irish Aran Islanders in the Films of Robert J. Flaherty. Open Library of Humanities, 9(1).

Lahtinen, T. 2020. Arctic Wilderness in Zachris Topelius’s Fairy Tale “Sampo Lappelil”. The Arctic in Literature for Children and Young Adults.

Lidchi, H. 1997. The poetics and the politics of exhibiting other cultures. Representation: Cultural representations and practices.

Lowenthal, D. 1993. Memory and oblivion. Museum management and curatorship, 12(2): 171-182.

McCannon, J. 1997. Positive heroes at the pole: Celebrity status, socialist-realist ideals and the Soviet myth of the Arctic, 1932-39. The Russian Review, 56(3): 346-365.

Medby, I.A. and Dittmer, J. 2021. From Death in the Ice to life in the museum: Absence, affect and mystery in the Arctic. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 39(1): 176-193.

Mignolo, W.D. and Walsh, C.E. 2018. On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis. Durham: Duke University Press.

Miller, J. 2017. “Bare Life and Bear Love,” in Critical Norths: Space, Nature, Theory. University of Alaska Press, p.119-135.

Miller, J.C. and Wilson, S. 2022. Museum as geopolitical entity: Toward soft combat. Geography Compass, 16(6): e12623.

Peers, E., Marsh, F. and Lund, P. 2020. Decolonising the SPRI library: position paper, pp.1-4.

Powell, R.C. 2023. Geography, Anthropology, and Arctic Knowledge-Making. In The Cambridge History of the Polar Regions, pp.279-301.

Powell, R. and Dodds, K. 2010. Knowledges, resources and legal regimes: the new geopolitics of the polar regions. Polar Record, 46(4): 375-376.

Powell, R.C. and Dodds, K. (Eds.) 2014. Polar geopolitics? Knowledges, resources and legal regimes. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Quijano, A. 2007. Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural studies, 21(2-3), pp.168-178.

Radcliffe, S.A. 2022. Decolonizing geography. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Radcliffe, S.A. 2017. Decolonising geographical knowledges. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42(3), pp.329-333.

Ray, S.J. and Maier, K. (Eds.) 2017. Critical Norths: Space, Nature, Theory. University of Alaska Press.

Reid, J. 2019. Narrating indigeneity in the Arctic: scripts of disaster resilience versus the poetics of autonomy. Arctic triumph: Northern innovation and persistence, pp.9-21.

Ridanpää, J. 2007. Laughing at northernness: postcolonialism and metafictive irony in the imaginative geography. Social & Cultural Geography, 8(6): 907-928.

Ryall, A., Schimanski, J. and Wærp, H.H. (Eds.) 2010. Arctic discourses. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Saldanha, A. 2007. Psychedelic white: Goa trance and the viscosity of race. U of Minnesota Press.

Said, E.W. 1978. Orientalism. Vintage.

Sakakibara, C. 2010. Kiavallakkikput Agviq (Into the Whaling Cycle): Cetaceousness and climate change among the Iñupiat of arctic Alaska. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 100(4): 1003-1012.

Stoddart, D.R. 1989. A hundred years of geography at Cambridge. The Geographical Journal, 155(1): 24-32.

Stuhl, A. 2013. The politics of the “New North”: putting history and geography at stake in Arctic futures. The Polar Journal, 3(1): 94-119.

Tam, C.L., Chew, S., Carvalho, A. and Doyle, J. 2021. Climate change totems and discursive hegemony over the Arctic. Frontiers in Communication, 6, p.518759

Toivanen, R. 2019. European fantasy of the Arctic region and the rise of indigenous Sámi voices in the global arena. Arctic triumph: Northern innovation and persistence, pp.23-40.

Tolia-Kelly, D.P. 2016. Feeling and being at the (postcolonial) museum: Presencing the affective politics of ‘race’ and culture. Sociology, 50(5): 896-912.

Tolia-Kelly, D.P. 2019. Rancière and the re-distribution of the sensible: The artist Rosanna Raymond, dissensus and postcolonial sensibilities within the spaces of the museum. Progress in Human Geography, 43(1): 123-140.

Tolia‐Kelly, D.P. and Raymond, R. 2020. Decolonising museum cultures: An artist and a geographer in collaboration. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45(1): 2-17.

University of Cambridge. 2022. University of Cambridge Advisory Group on Legacies of Enslavement Final Report. [online] Available at: https://www.cam.ac.uk/about-the-university/advisory-group-on-legacies-of-enslavement-final-report [Last Accessed 17 April 2024]

Vawda, S. 2019. Museums and the epistemology of injustice: from colonialism to decoloniality. Museum International, 71(1-2): 72-79.

Waterton, E. and Smith, L. 2010. The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage. International journal of heritage studies, 16(1-2): 4-15.

#Write for Routes

Are you 6th form or undergraduate geographer?

Do you have work that you are proud of and want to share?

Submit your work to our expert team of peer reviewers who will help you take it to the next level.

Related articles