Volume 4 Issue 1

By Thomas York, University of Leicester

Citation

York, T. (2024) A Topo/graphy of The Garlic Farm, Isle of Wight: Reproducing a Marketplace. Routes, 4(1): 39-49.

Abstract

The Garlic Farm (Isle of Wight), a site where garlic is produced then presented as various commodities in a farm shop, is a place with a unique consumer experience: it is appropriate to analyse it as if it were a marketplace, a place of ‘brisk commodity trade…lively, vibrant and buzzy’ (Coles, 2021, 3). Using the methodological framework of topo/graphy, this article examines some of the social, economic and material processes that reproduce this (market)place. Sensory engagements are fundamentally important in the marketplace, as they contribute to greater familiarity with products. The education centre is a place where commoditisation is catalysed by social relations. Both of these processes connect with the wider idea that the farm shop connects consumers with different places of production, both of garlic farm produce and wider global and regional (market)spaces, which in turn contribute to the reproduction of this place.

1. Introduction

Figure 1 – The entrance.

Barrelling down Lime Kiln shute is a white-knuckle ride. It is impossible to imagine that at the bottom of this country road – so far removed from the seaside towns it leads to – there is a vibrant, bustling, sensuous consumer experience, complete with an education centre and an overflowing car park (Field notes, October 2021).

*

Having visited The Garlic Farm multiple times, as a customer and researcher, it is a fascinating site to experience. The commodities, the built environment and the experience of this farm on the rural Isle of Wight are so intimately connected to economic geography scholarship that I believe it is appropriate to analyse it as a marketplace. Using Coles’ (2021) methodological framework of ‘topo/graphy’ (place/writing), I address concepts alongside findings from fieldwork at The Garlic Farm to critically analyse the reproduction of this marketplace, comprehensively ‘writing the place’. This methodology works from the concept that place is ‘open to its interconnections with other places, but bounded by the interrelation of its constituent material, social, sensual and discursive ‘realms’’ (Coles, 2021, 11): in this analysis I address all of these ‘realms’ as well as the Garlic Farm’s wider connections with other ‘marketspaces’.

The Garlic Farm is exactly what it says it is and more, a farm where garlic is grown and sold in a multitude of different forms, with a variety of things to do, see, touch, smell and taste. The economic activity of the site is concentrated in the farm shop (with an attached education centre), the restaurant and the allium café. This analysis of this marketplace is based around economic transactions, and is concentrated on my personal experience in the farm shop and the education centre.

I begin by briefly introducing the Garlic farm before reflecting on the sensory experience on site. I address the signs within the marketplace, which I argue are particularly important in the wider experience of visiting the Garlic Farm. This leads to analysis of the different ‘marketspaces’ that The Garlic Farm is part of before I conclude with an overall assessment of my findings. In terms of methods, I use field notes as the primary source of ‘data’ to inform analysis in this topo/graphy: these field notes are particularly important in representing the sensory experience of being in The Garlic Farm, but are used in constructing all points. Each of the points I make is supported by photos taken by me (2021) and my sister Sophie, who took photos of food for a GCSE food technology project in 2019 – these present essential visual aspects for analysis.

2. Sensory Engagements: Knowledge and Familiarity

Figure 2 – The tasting experience. Source: S York, 2019.

Figure 3 – Various Garlic Farm products. Source: S York, 2019.

Ducking under the beam and through the doorway, I’m hit by the strong smell of garlic. The volume of soil-encrusted bulbs – all shapes, sizes and colours – gives the room that pungent smell that some love and many hate. The room is set out in rows of tables, each covered in a colourful assortment of jars, bottles, bags and baskets. The sensory engagement is currently reduced, with the Covid-19 pandemic responsible for the change: on previous visits there had been tasting pots and cups, with customers encouraged to try The Garlic Farm’s produce. However, the shop is just as crammed with people and food as before, with the addition of facemasks and seals on all jars and bottles. From pickle and ketchup to beer and vodka, the common ingredient in everything is garlic… Outside the café, there is a large sign bearing a quote by William Shatner: ‘stop and smell the garlic, that’s all you have to do’ (Field notes).

*

Pink writes that one can think of analysis of sensory findings as a way of making ethnographic places, a sensorial process of connecting experiences with scholarly practices (2015: xiv): engagement with the senses is important for place-making. Low’s work, describing ‘sensory invasions’ by migrants in Singapore, examines the way in which the sensory formulates communities through exclusion and construction of otherness with respect to place (2013: 234), whilst Coles refers to the way in which smell becomes a marker of place for food, commoditising geographical representations of places of production (2021: 121). In the case of The Garlic Farm, the smell of garlic in the shop forms a key part of what consumers will associate with the place – the key ingredient in the food. Also, this natural aroma and the sight of dirty ingredients presents the natural conditions of the food’s production (Feagan, 2007: 25), connecting the consumer with places of the foods’ production. Furthermore, this sensory experience at The Garlic Farm is used by the management to facilitate greater engagement with the produce. In an ethnography of Ridley Road Market in Hackney, Rhys-Taylor (2013) uncovers the importance of smell and taste in the marketplace as customers develop an embodied familiarity with sensory engagements, generating key forms of exchange. Through the employment of smell and taste in the farm shop, I would argue that the organisers of this marketplace have been able to create a greater sense of familiarity with the produce in the shop, both through the ability to see the raw material that goes into the produce, and the opportunity to become quite literally sensorially familiar with the finished product itself. This familiarity encourages economic activity in the farm shop, which in turn contributes to the reproduction of the marketplace.

3. The Education Centre: Signs and Performance

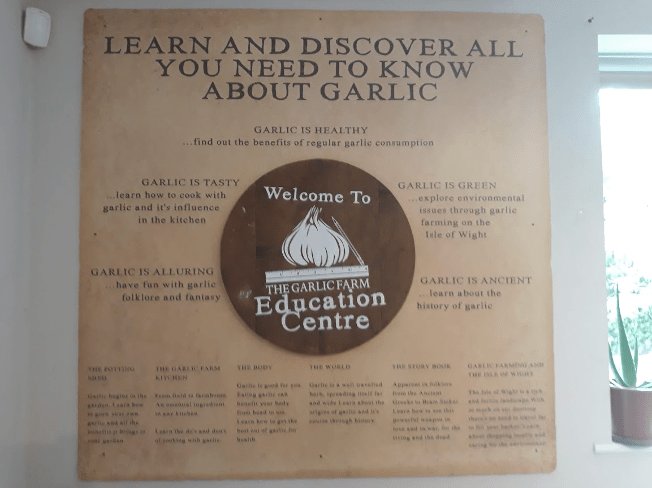

Figure 4 – ‘The Education Centre’.

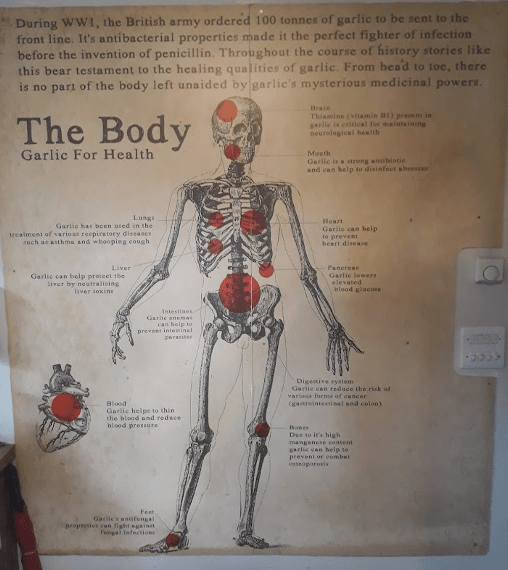

Figure 5 – Garlic and health.

Adjacent to the farm shop is the education centre, another maze of tables laden with Garlic Farm products, but with one difference. The walls are covered with information: a calendar showing the best times to plant and harvest various types of garlic, historical information about garlic on the Isle of Wight and beyond, recipes featuring Garlic Farm produce…Clearly significant time and thought has gone into the production of these signs. The education centre also has multiple staff members walking around, talking about displays with customers. One man standing by the calendar can be heard…‘this variety is on offer…it’s a great bulb because it’s a winter crop…come next spring I’ll be digging it up and putting it in soups.’ (Field Notes).

*

The education centre can be analysed as part an ‘assemblage of a distinctive visual material culture…a visual economy of consumption’ (Coles, 2014: 520). It is distinct, more a museum exhibition than part of a farm shop. Its purpose is to frame idealised worlds in which Garlic Farm products are beneficial in consumers’ lives: the sign showing the human body portrays idealised notions of health that directly encourage the consumption of the commodities in the marketplace, thus contributing to its reproduction. These signs operate as advertisements, transmitting messages that become part of attitudes towards products (Sack, 1988: 643). In this way, customers can gain greater understanding of some of the histories and geographies of garlic. These signs demonstrate what Featherstone describes as ‘the rapid flow of signs and images which saturate the fabric of everyday life in consumer society’ (2007: 66). The signs in the education centre constitute this ‘rapid flow’, providing all manner of garlic-based information that produces fetishized notions of the benefits of the commodities on site.

Another important aspect of being in the education centre is the interaction between vendors and customers. I observed the role of Garlic Farm staff member to be a ‘conduit of information’ about food being sold (Coles, 2021: 110). In accordance with previous research in marketplaces, it is important to consider how this performance of sociality is deployed to sell. Coles observes this in Borough Market, an experience that is predicated on presenting consumption and the exchange of money as an afterthought, obscured by the precisely calculated embedded social relations between the vendor and the customer (Ibid., 2021: 111) – it is also important to consider that these relationships can be overlaid with sentiments of trust (Granovetter, 1985: 490). Examples of this that I observed in the education centre at The Garlic Farm show the way that sociality is deeply implicated in the commoditisation of the products in the farm shop (Coles, 2021: 111) and its reproduction. Ultimately, ‘the modern world of goods is predicated upon information and visibility. Remove knowledge, publicity and advertising, and the itch to consume does not merely subside…it becomes unthinkable’ (Brewer and Porter, 2013: 6). In the education centre, this information is not only visible, but enhanced and embodied by fetishized social relations between staff and customers.

4. (Market)Spaces and The Garlic Farm

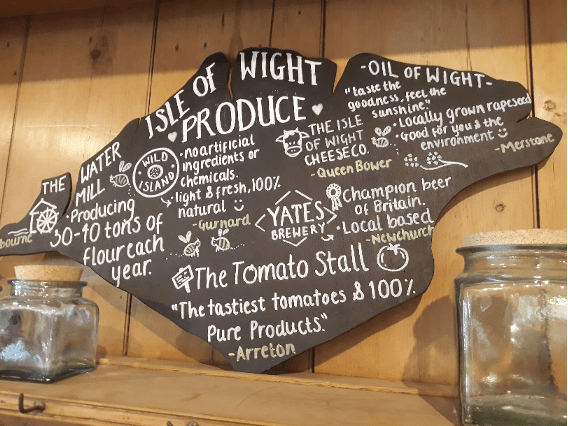

Figure 6 – Isle of Wight map, prominent in the shop.

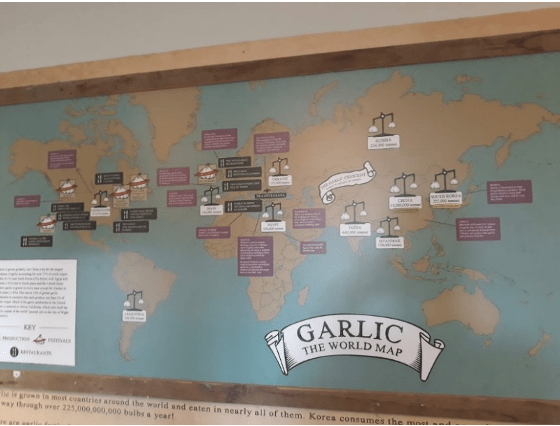

Figure 7 – important Garlic places.

Explicit references to food geography can be found in the marketplace. A wooden, hand-painted map of the Isle of Wight, showing food and drink produced on the island…a map on the wall showing key Garlic places around the world, including parts of the world that produce the most, and garlic-specific restaurants in London and California… (Field Notes).

*

Within contemporary geography, place has become understood as a product of relationally constituted processes embedded in broader interrelations, as opposed to being fixed and self-contained (Jessop, Brenner and Jones, 2008: 390; see Massey, 2005). In accordance with this viewpoint, it is important to consider The Garlic Farm’s topological position as a (market)place within wider (market)spaces, as a meeting point in space, constituted through spatial flow and movement (Malpas, 2012: 229). The two topologies I explore here are represented in the images above, the first of which involves numerous references to ‘Isle of Wight’ or ‘IoW’. The farm shop sells products from The Garlic Farm, as well as produce from various Isle-of-Wight-based businesses – it becomes an economic arena for local business. The constant references to ‘local’ in the food are important in invoking associations with better quality (Holloway and Kneafsey, 2000: 292): geographical meanings become embodied into food, constructing a marketplace that deals with food perceived as having greater exchange value. This is all based on social relations between producers of the local food and The Garlic Farm, which are key in establishing the place-to-place connections that construct this topology. The other marketspace that is presented to customers in the farm shop is the map showing sites of production, negotiation and consumption in a global garlic economy, with the Garlic Farm at the centre. Allen makes a relevant conceptual point, that ‘connections’ between places are key in composing the spaces of which they are a part, and are not simply lines drawn on a map (2011: 317).From my own position viewing this map, I imagine The Garlic Farm as a place of importance within an international garlic network of socioeconomic relations. This imagination could obscure the true quality of products in the marketplace, but it is an imaginary that contributes to how the marketplace is viewed. As I see it, this marketplace is a production of engagements with Isle of Wight and global garlic marketspaces, built upon vendor-vendor connections extending beyond the marketplace, made up of a multitude of embodied meanings contributing to meanings ascribed to the marketplace.

5. Conclusion

This topo/graphy has detailed the processes experienced in The Garlic Farm, all of which reproduce this particular marketplace. Sensory engagements in the farm shop connect customers to places and geographical imaginations of the natural conditions of its production, and contribute to familiarity with products. The visual economy of the education centre presents idealised imaginations of the effect of commodities, and vendors are important in performing sociality based on trust, encouraging consumption in the marketplace. Finally, presentation of wider topologies that The Garlic Farm is connected to is key to analysing the marketplace, but one has to first examine marketplaces like The Garlic Farm to discover social relations between vendors that form these marketspaces. To conclude, the marketplace is formed through various social, discursive and geographical relations: analysis of these linkages is important in constructing a broad economic geography, since they enable greater understanding of the connections between places that form an economy. Future research in this area could produce interesting results in numerous other sites of social/economic interactions. This work is based around food, as is Coles’ (2021) work in Borough Market: it would be exciting to see place-based topo/graphical research focussed on the trading of commodities like services.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr Ben Coles and Dr Angela Last for their guidance in helping me develop an original idea into a coherent article. This work is dedicated to all members of staff at the University of Leicester who supported me through my degree – thank you all.

References

Allen, J. 2011. ‘Making space for topology. Dialogues in Human Geography, 1(3): 316-318.

Brewer, J. and Porter. R. (Eds.) 2013. Consumption and the World of Goods. Abingdon: Routledge.

Coles, B. 2014. Making the marketplace: a topography of Borough Market, London. cultural geographies, 21(3): 515-523.

Coles, B. 2021. Making Markets Making Place: Geography, Topo/graphy and the Reproduction of an Urban Marketplace. Springer International Publishing.

Feagan, R. 2007. The place of food: mapping out the ‘local’ in local food systems. Progress in Human Geography, 31(1): 23-42.

Featherstone, M. 2007. Consumer Culture and Postmodernism. (2nd edition) London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Granovetter, M. 1985. Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3): 481-510.

Holloway, L. and Kneafsey, M. 2000. Reading the Space of the Farmers’ Market: A Preliminary Investigation from the UK. Sociologia Ruralis, 40(3): 285-299.

Jessop, B., Brenner, N. and Jones, M. 2008. Theorizing sociospatial relations. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26: 389-401.

Low, K.E.Y. 2013. Sensing cities: the politics of migrant sensescapes. Social Identities, 19(2): 221-237.

Malpas, J. 2012. Putting space in place: philosophical topography and relational geography. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 30: 226-242.

Massey, D. 2005. For Space. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Pink, S. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. (2nd edition) London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Rhys-Taylor, A. 2013. The essences of multiculture: a sensory exploration of an inner-city street market. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 20(4): 393-406.

Sack, R.D. 1988. The consumer’s world: place as context. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 78(4): 642-664.

#Write for Routes

Are you 6th form or undergraduate geographer?

Do you have work that you are proud of and want to share?

Submit your work to our expert team of peer reviewers who will help you take it to the next level.

Related articles